Erik Gjems-Onstad (EGO) was born in Oslo on February 22 1922 but spent his childhood in Asker, a small community half way between Oslo and Drammen.

The son of a lawyer father and architect mother he was taught from an early age to speak out and have strong opinions. His first ambition was to be a naval officer so at 15 he signed on as a deck-hand to fulfil the requirement for the first step in this direction. It was a short step – after six months he had to quit – unable to master the physical effects of the pitching and rolling at sea.

Back as a landlubber he continued schooling, cycling and scouting, all with an enthusiasm that bode well for the future. In 1939 he became the Norwegian Junior Cycling Champion and his scouting skills came in useful when, heeding the looming war signs in Europe, local patriots asked him to teach map-reading at an unofficial military training course. In February 1940, one of his scout colleagues, Hans Chr. Mamen volunteered for ambulance service in Finland. This made “a very strong impression” on Gjems-Onstad 1 who began to ‘be prepared’ by participating in realistic training with his scout-troop in the hills and forests around Asker.

Invasion

The war clouds in Europe grew and Gjems-Onstad remembers that on April 6 he and a friend shared an ominous feeling that something dramatic was about to happen. It was Saturday so they trekked into the hills and spent a cold night in a tent pitched in the snow – a tough training session. On Tuesday morning, April 9th, the Gjems-Onstads watched as “…large, grey military aircraft with black and white crosses on their wings…came skimming over the tops of the fir trees in front of the house.” The planes, bearing troops to support the sea invasion, landed at Fornebu airport which, on a clear day, could be seen from Gjems-Onstad’s home.

They knew that the ‘planes were a prelude to war, but since the radio was silent they decided carry on as usual: father took the train to Oslo and Erik cycled to his school, the Oslo Cathedral School. Here he heard that one of his teachers had joined the military resistance, but otherwise, news was scarce. Some of the students showed up wearing NS 2 armbands, others wore NS uniforms. He decided to cycle home but on the way, in the centre of Oslo, he stopped to watch a column of German troops march down Karl Johan’s Gate. “It was a strange feeling to see Norwegian mounted police escorting these soldiers down Oslo’s main street.” 3 A photograph in the newspaper Aftenposten later that day showed several young men standing with bicycles watching the oncoming troops – one of them was probably Gjems-Onstad. “Probably” is my word; Gjems-Onstad is certain that he was the cyclist and his detailed analysis of the day, and the German troop movements, seem to support his claim.

The day after – Panic Day 4 – EGO cycled to Oslo again to visit a relative. Several other students gathered there. They discussed the invasion and the speech Quisling had given the evening before. They argued about what to do but without reliable information to guide them, they decided to wait for an official communiqué from the government. They gathered around the radio to hear the Prime Minister, Johan Nygaardsvold 5 , give his report from Elverum. In his office at home in Asker almost seventy years later, Gjems-Onstad read this speech to me in a clear, modulated, voice. Then he looked at me questioningly, expectantly. I don’t know what he expected but he didn’t wait long: “Not a word of encouragement, not the slightest incitement to DO something. We were all completely disappointed” he said. In his written reminiscences in 1991 6 he was more specific: “The proclamation from the government was blah, blah – not a single word about mobilisation, defence, battle, or war. The announcement was a terrible disappointment for that group of youngsters and the general impression was that the government didn’t approve of opposition to the invaders.”

Resistance

In spite of their disappointment some of the youngsters made sporadic attempts to join the Norwegian forces. EGO and a friend Georg Smiseth got as far as north Trøndelag but the fighting there was over before they made contact with the military. Back in Asker, he witnessed the early birth spasms of the Resistance movement – and sadly said goodbye to a friend who continued to be a member of the hated NS.

The country was almost paralyzed by the shock of the invasion and resultant occupation. Throughout the summer, however, there had been hope that some form of independent government would emerge. These hopes were dashed by the dismissal of the ‘Administrative Council’ and the banning of all political parties, except NS, on September 25. These were the last straws – the battle lines were drawn.

In Asker the 1st Skaugum scout troop quickly took the initiative. Hans Chr. Mamen, who had returned from Finland, Gjems-Onstad and Carl Emil Petersen were among the ringleaders. They posted placards encouraging people to boycott athletic arrangements organised by the ‘new’ regime and disrupted a meeting of the local NS party. For the latter action several were arrested and fined. They talked about organizing groups and Gjems-Onstad told Mamen that he had met a Norwegian officer who had been in England and was now back in Norway to organise resistance. His orders were: form groups, practise orienteering, and generally, keep in shape. (Later, EGO admitted to Mamen that this had been just a bluff – to rally his colleagues to action.) 7

The bluff may have been effective – the resistance movement in Asker grew rapidly and with prominent enemies as neighbours8, both opportunities and dangers were manifold. Earlier in September EGO had matriculated at the University in Oslo, started his law studies, and met other students actively seeking ways to resist the new regime. The ‘new regime’ was already organised – on September 24th a group of ‘hird’9 faced a crowd of students in front of the University. EGO called them “traitors”; he was pounced upon, and beaten up but not seriously injured. A regular battle followed. Perhaps this was the trigger for EGO’s commitment to the fight for freedom?

The fight was not only physical. In Asker many YMCA members were engaged in resistance activities. The father of one of these, an engineer Albert Hjort, had created some plans for two inventions: an impact-grenade and a mine-sweeping apparatus. The questions were: could they be of use to the allies and how to get the information to the allies in the UK? It was agreed that one man should take the north-sea route to Scotland and another should travel via Stockholm, both in attempts to deliver the plans to British authorities.

To Sweden

On February 28 1941 Erik Gjems-Onstad left his home in Asker, destination Stockholm. He didn’t return again until June 1945. With the help of an uncle who lived in Skasen he crossed the border into Sweden and was promptly arrested by the Swedish police. After a few days in Torsby jail he arrived in Stockholm. Nobody at the Norwegian legation showed any interest in engineer Hjort’s inventions so EGO contacted the British legation. Here he met Major Malcolm Munthe who was keenly interested and who immediately offered his assistance – and would EGO consider returning to Norway?

EGO would, indeed – but on March 25th he was arrested again. Major Munthe’s anti-German activities, along with his contacts, had been exposed. In the uncertain atmosphere of neutral Sweden at that time this could only mean one thing – EGO became a ‘guest’ of the Swedish government for the next 10 weeks. “On May 23rd 1941 my friend King Gustav V decided he didn’t want to feed me any longer so he banished me from the land and told me never to come back,” said EGO to me in an ironic voice and smiling eyes. After several false starts, one more arrest, and 6 months uncertainty he was finally assigned a seat on a ‘plane to England 10– where one of the first officers he met was his ‘friend’ from Stockholm, Major Munthe.

England

Since the summer of 1940, Norwegians had gravitated to the United Kingdom (UK) by a variety of routes: across the North Sea, from Stockholm, via Russia, India, China, Canada, and the United States. Their motive was to participate in the fight against Nazi Germany. By the time EGO arrived, a system had been organised and the Norwegian Independent Company No. 1(Nor.I.C.1) established. An eye test determined that EGO needed glasses which, in those days, took time to produce. But at last they arrived: he completed his basic training, moved on and graduated as a radio operator and earned his ‘wings’ for parachute-jumping. He then returned to STS 26 (Special Training School No.26), a holding school in Scotland where men waited for postings or further training.

Private Erik Gjems-Onstad, like most of his colleagues, had only one thought as he ‘waited’ in Scotland –to get into action. In early January 1943 he was called into the office and told to report to London – a 14-15 hour uncomfortable train journey away. Here he again met Major Munthe who asked if he ‘knew’ Trondheim. Since he had passed by that way once, on his attempt to join the Norwegian forces in 1940, he unhesitatingly said “yes”. He gave an immediate “yes” to the next question: “Will you go to Trondheim?” With that, Munthe introduced EGO to his new boss and travelling companion – Lt. Odd Sørli. Within minutes Sørli had accepted EGO as his radio operator for the vitally important operation LARK. He neglected to tell EGO that the previous radio operator, Evald Hansen, had been captured and had died after torture in Falstad prison.

A hectic day followed in London: from the special Norwegian depot he collected clothes, instructions and most important of all, three radios. He needed 3 radios so that he could send from 3 different locations thus minimising the risk of detection. Weapons and ammunition, too, were on the ‘shopping list¨ and a Colt 7.65 became EGO’s best friend – he never left home without it – and it was always under his pillow when he slept. One item or items – there were two of them – took little space: two small pills, liquid in rubber capsules, contained cyanide potassium. If swallowed by accident they would pass through with no effect, but to bite into one meant almost instantaneous death. These were the escape of last resort for many prisoners who could no longer stand the torment of Gestapo torture.

Scotland

That evening, EGO boarded the train for Inverness with Lt. Odd Sørli. The officer chose to sit with the private instead of travelling first class. They had much to talk about and got to know each other well. Sørli was more of a father figure than a commanding officer so the partnership got off to a good start. In cold, windy Inverness their pilot was uncertain of the flying conditions to the Shetlands but finally decided to take off. It was a miserable flight. Sørli and Gjems-Onstad were air-sick and embarrassed as the only military among several civilians. On the drive to their billet they felt that the wind tried to blow them off the road, but they arrived safely at their country estate. ‘Flemington’ was a fine old manor presided over by a British officer and his Norwegian wife. The men felt at home here, they lived well, practised shooting on the range, and roamed the glens in search of grouse. The stay could have been enjoyable – but all were bored and impatient to get started on their real tasks – fighting against the Germans in Norway. Finally they received orders to get ready for departure and on February 22, (EGO’s 21st. birthday,) they were driven to Scalloway.

North Sea Crossings

Scalloway, in the south-west of Shetland, was base for the Norwegian Independent Naval Unit No. 1 – better known as The Shetlands Gang. From here Norwegian fishing boats and seamen carried arms and men to Norway for the growing resistance movement. Their return ‘cargo’ consisted of men and women fleeing from the invaders in Norway – mostly to join in the fight against them.

The fishing-smack “Harald II” was waiting for Odd Sørli and Erik Gjems Onstad at Scalloway. The skipper, Capt. Hillerøy, had made several crossings but this was to be his first as captain – and, as it turned out, a real test of his seamanship. The crew of six had many seasons and journeys in their logs and the land-lubber Linge commandoes had complete faith in these experienced sea-men. EGO was surprised to see oil-drums fettered to the side-rails but when he mentioned this to Odd he got only a smile in response. The vessel had scarcely left the port before the skipper ordered “all hand on deck for shooting tests.” Each crew-member ran to his oil-drum, loosened the top, and pushed it aside to reveal a ready-to-fire machine-gun – from innocent fishing-smack to death-spitting gunboat in no time at all. No wonder Odd had smiled.

Neither Odd nor EGO was in the mood for smiling a couple of hours later, when, shortly after departure they began to feel sea-sick. They went below to their cabins. It was difficult to sleep or rest. The loudspeaker over their bunks regularly broadcast Morse signals: QRU, QRU; the code signal for: “we have no messages for you.” They crabbed their way on deck only to see mountainous waves and to be drenched by water crashing aboard. The wind had increased to full storm and the captain decided it was no use continuing. “Harald II” limped slowly westward with its two passengers lying on their bunks wet-through and so disappointed. Both they, and the crew, had been almost without food for two days – two days of hell.

Skipper Hillerøy tried to comfort them by saying that now they had experienced a real storm, the next trip would seem like a Sunday outing. They made landfall near the northern tip of Shetland and to save time decided not to return to base. After two days the weather improved and they began their journey again. With a following wind they made good progress. They were able to test the machine guns again, practise their pistol-shooting, and even enjoy their meals. But it didn’t last; as they approached the Møre coast the wind increased and again they were battling a full storm. Not only that, but German searchlights and artillery emplacements prevented them from seeking lee among the skerries. There was no alternative – westward again – this time, after 3 or 4 days, the boat sprang a leak. Even with pumps working full time the skipper couldn’t guarantee that they would stay afloat if the leak increased. And without lifeboats – or even life-belts, they knew what that meant. As a last resort they decided to break radio silence to send out SOS signals. The reply came quickly – help will be on the way as soon as weather permits. Next day five fighter aircraft were searching for “Harald II”. On the evening of March 1 she was back in Scalloway with a sodden crew and passengers – and a completely destroyed cargo of radios, provisions, and weapons.

New weapons, provisions, and radios had to be supplied from London so it was March 12 1943 before they were ready again. In a larger vessel, Andholmen, with a different crew they set off again, this time heading for Kristiansund. Two days later in the evening, they sighted land but they were much further north than anticipated –west of Namsos. They decided to take a chance on landing and steered towards a house beside a small inlet. It was almost dark but as they came nearer Odd pointed out two radio masts on a hill behind the house. Before they had time to worry about German soldiers, another problem arose: They ran aground.

Landfall

The situation was desperate: they were aground, within sight of an enemy radio station, it was dark, windy, and cold. Luckily the tide came in and they floated free. They decided to seek assistance at the house. If Germans were billeted there, Odd and EGO would pretend to be fishermen needing help. If a Norwegian opened the door they would tell the same story and they were 98 percent certain that he or she would not give them away. Just in case, the two Linge men kept their hands on their weapons.

Trader Peter Løvsnes opened the door, listened to their cock and bull story about needing help with directions, and said “You’ve come from the west I suppose.” He was as eager as they were to fight against the invaders. He said that Odd and EGO could take the north-bound steamer to Namsos. It was due in a couple of days and he knew the captain would pick-up all their equipment and ferry it to Trondheim on the return trip. Best of all: the radio station was not in operation – there were no Germans in the neighbourhood. During the night they removed their supplies from Andholmen and early next morning she headed westward again – mission accomplished.

The local steamer arrived on schedule and EGO, who had been away from Norway for two years, felt apprehensive when he saw the 20-30 uniformed Germans on deck – finally, the enemy. Odd and EGO waited in the house while Løvsnes went on board to speak with the captain. At the all-clear signal they sauntered down to the quay, hands in pockets (holding their pistols and grenades!), and climbed aboard. Løvsnes met them and said they should go to their cabins. They shook hands, and after a quick “thanks for the help”, they went below. Capt. Rømen came shortly afterwards – he was anxious to hear the news from England and equally interested in helping them. Not only would he carry the supplies to Trondheim – he would make sure they got ashore safely.

At Namsos, Odd and EGO left the ship and boarded the train for Trondheim. So far their false papers had been accepted without question. At a German passport control at Grong there was an anxious moment. The guard looked long and carefully at Odd’s false identity card – it seemed like an age but was probably only seconds. Then, sharp and searching: “Border pass?” EGO thought that Odd might be about to draw his pistol, but no: “A border pass is not required for transit” he replied. The German handed back his card, took a quick look at EGO’s and the inspection was over. Odd Sørli’s calm reaction in such a critical situation further increased EGO’s respect for his boss. The rest of the journey was uneventful and the two men passed unnoticed through the central railway station in Trondheim.

Trondheim

It was EOG’s first visit to Trondheim but Odd had been born there, and was known as a member of the resistance. They were welcomed as old friends at a house in Singsaker. To their great surprise, in the living room, sat Nils Uhlin Hansen and Johnny Pevik – the two other Linge-men who had been sent from London – they had been at the waiting camp in Scotland with Sørli and EGO. After a short meeting, EGO was taken to another house, in Markveien – but not before Sørli had emphasised that a new stage had begun for Lark. Even without knowing anything about the current situation, EGO realised that London didn’t send 4 trained men to Trondheim without expecting some real activity.

The Beer family lived in the house in Markveien. Jens Beer was one of the key men in Milorg.The previous leader had been recently arrested.

Parkvein 26, Singsaker. At one period 3 Linge – men lived here.

He gave a brief outline of the events in Trondheim since Sørli had last been there. EGO remembered one sentence: “We will give you all the assistance you require but we draw the line at sabotage.” At the time this sounded negative to EGO, but as he got to know Jens and his men better, he realised that their attitude did not reflect weakness or apathy.

The 1942 state of emergency, arrests, and executions had shocked the whole of Trondelag and were still intimidating factors.

Next day EGO started hunting for an apartment or a room to rent. Trondheim, with its large student population, was not an easy place to find lodging. The influx of German military and civilians made it even more difficult. Finally, far from the town centre, he was offered a room in a large house owned by an army officer. It was sparsely furnished and completely lacking heat. Winter was fading away, it was the end of March: “… the coldest period I have ever experienced…. nothing to heat with, nothing warm to drink; just cold and unpleasant the whole day.”

EGO was to be the radio operator for Lark Blue. He rigged up an internal antenna in his ice-box of a room. His job was to encode and send Sørli’s messages to London, and receive and decode return messages. That was it – as Major Munthe had warned him in London, “You must have the patience of a saint. You must remain quiet, quiet as a mouse, for many, many months.” His first attempts to make contact with London failed. Three times weekly, at a set, but varied time, he sent out his call signal and listened for a reply. If contact wasn’t made within 9 minutes he had to close down and wait two days for the next scheduled time. He was cold, disgruntled and disappointed, day after day, alone with his thoughts of being a failure, first by losing valuable equipment and then by not making contact with London.

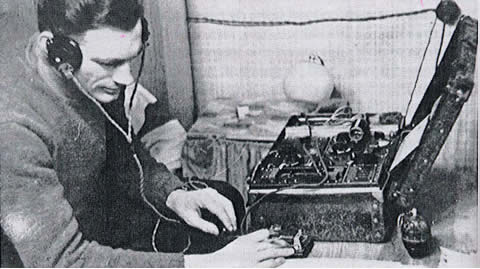

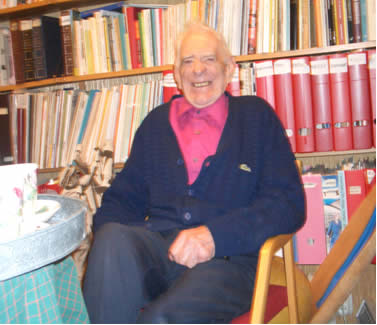

Erik Gjems-Onstad. Radio Operator. From the film Det grodde fram

The entire operation ruined because of his incompetence. These were the thoughts of a lonely young man. He had told his landlord that he worked for a builder so he had to leave the house each morning with nowhere special to go. After many fruitless hours trying to contact London he realised that the internal antenna was the problem. With the help of a NTH student he found another location where he could string out an antenna over a roof – and, finally contact with London. Now they could begin…..

Counting the 130 men at NTH, 300 in Trondheim, and 20-30 in each of the other groups, the Milorg organisation in Trøndelag comprised 8 – 900 men at the beginning of summer 1943. Many of these had received weapon training in 1942 after a supply of arms had been shipped from England in January 11 , but there had been no centrally-led training in 1943. A great deal of information about German army and naval installations had been forwarded to the Allies and large dumps of arms and ammunition had been established throughout the region.

Expectations of an Allied invasion were great – but so was the uncertainty and after the intense activity of 1942 and early 1943 came a period of quiet. At the same time, the risk of exposure increased, partly because of the hidden weapons but even more because the Gestapo, and Henry Oliver Rinnan, had built up an underground informer organisation – Lola – almost as large as Milorg itself. Meanwhile, traffic on the radio increased. By the beginning of summer 1943, EGO’s three radios, in three different locations were in connection with London 4 times weekly. The volume of traffic was rather more than security called for, but London wouldn’t cut back. Not even when a double-agent reported that the Gestapo claimed to have a bearing on a radio transmitter in Trondheim. However, to minimise the risk to EGO, London agreed to send “blind” – that is, EGO should not answer their call signal but only listen and receive messages. His own transmissions were restricted to short, urgent, messages.

This self-imposed radio silence meant that the radio connection with the British Legation in Stockholm was broken. However, this was replaced by a train driver on the Meråker line who became a reliable courier for Lark. On almost every journey he had messages to and from Stockolm. There were many and they were in code. EGO could often sit for 6 – 8 hours at a stretch decoding and listening. In addition to the Home Station at scheduled times, he listened to the BBC for “special messages” and to the illegal ‘Norwegian’ transmitter “Freedom”.

From his freezing one-room billet, EGO had moved into Beer’s house. Martin Beer and Ole Dahl became his couriers and assistants. The Beer home was his ‘listening post’ but he transmitted from a student apartment in another part of town. Life had become more comfortable and he had even a little time for relaxing and socialising – with, among others, Ragna, the sister of Odd’s fiancé. In London, the spectre of Tirpitz still haunted Allied thoughts and created tasks for Milorg, but the warship had left Trondheim and never came back. Sørli’s other activities with Milorg included the movement and hiding of weapon stores and the continuous recruitment of men for the organisation.

Assassination Attempts

Strengthening the organisation was one thing; protecting it against the Gestapo and informers was another. The Allied offensives in Europe and Africa meant that there would be no major attack on Norway for the foreseeable future so the emphasis must be to maintain Milorg’s strength for the final phase of the war. Odd Sørli had gone to Stockholm to discuss the situation and had reached an agreement to defend the organisation by targeting the informers.

Henry Oliver Rinnan

In Stockholm they hatched out a plan to lure Henry Rinnan to a meeting close to the Swedish border, kidnap him, press him for information, and then liquidate him. Easier said than done – but with anonymous letters and newspaper notices the attempt was made – to no avail; it appeared that Rinnan wouldn’t rise to the bait so they reverted to Plan B. Johnny Pevik Brodtkorb-Danielsen, Brekke, and Gundersen left Stockholm with orders to liquidate him. In the meantime, Rinnan responded to the first plan and four more men were sent from Stockholm in an attempt to make sure that one of the plans worked. Both groups, travelling separately overland, ran into serious snow storms but eventually arrived in Trondheim about September 20th. Meanwhile, EGO was the only Linge agent in Trondheim, but neither he, nor anyone else in Lark or Milorg, had heard anything about the assassination plans. Johnny Pevik had orders to avoid contact with EGO and Lark, but one day, by chance, they met on the street.

Pevik felt that he had to tell EGO about his assignment, especially because he had a problem: Brekke had disappeared. Pevik guessed that he had gone to find one of Rinnan’s brothers who didn’t approve of Rinnan’s work. Maybe Brekke was trying to enlist his help? When Brekke turned up again, after the October 6 assassination attempt, EGO urged an immediate court-martial. Pevik thought this too drastic and simply ordered Brekke back to Stockholm. He ignored the order and remained in Trøndelag – where he soon became an active informer for the Germans.

On October 6 1943, Pevik, Danielsen and Gundersen waited outside Rinnan’s home. Details of the events that followed are uncertain because various reports are conflicting. What is certain is that one of Rinnan’s aides, Bjørn Dolmen was shot and wounded, that shots were fired at Pevik’s men wounding Gundersen, and that Rinnan escaped unharmed. There has been speculation that Rinnan had been warned of the assassination attempt, possibly by Brekke, but this has not been proved. Pevik knew a ‘safe house’ nearby and took the injured man there – he didn’t know that this house was EGO’s transmitting station. A worried EGO came and had to act as a doctor and clean out the wounds. After a few days, and the treatment by a real doctor, they were able to get Gundersen on the train to Oslo – and out of danger. Dolmen recovered after two weeks – Rinnan was unharmed – the assassination attempt had failed.

In the middle of October, Pevik and Danielsen headed for Namdal as forest workers with false identity papers. At Harran they came in contact with a reliable group but the local Milorg men were not sure about the newcomers. Were they to be trusted? Were they Rinnan’s men? Mistrust and uncertainty pervaded the atmosphere in Trøndelag at that time because of the effectiveness of Rinnan’s informer network. The local Milorg leader checked with his contact in Stockholm who replied that he knew of no British agents in their district. Pevik and Danielsen were thus branded as provocateurs and denounced to the Gestapo. Danielsen was away in the village when the Germans surrounded the cabin. He escaped to Sweden. Pevik was arrested.

In the middle of October, Pevik and Danielsen headed for Namdal as forest workers with false identity papers. At Harran they came in contact with a reliable group but the local Milorg men were not sure about the newcomers. Were they to be trusted? Were they Rinnan’s men? Mistrust and uncertainty pervaded the atmosphere in Trøndelag at that time because of the effectiveness of Rinnan’s informer network. The local Milorg leader checked with his contact in Stockholm who replied that he knew of no British agents in their district. Pevik and Danielsen were thus branded as provocateurs and denounced to the Gestapo. Danielsen was away in the village when the Germans surrounded the cabin. He escaped to Sweden. Pevik was arrested.

When the local contacts saw him paraded through the district in chains they realised that they had been the victims of a terrible misunderstanding. 12 Pevic was taken to Gestapo headquarters in Trondheim. How he managed to survive the horrors of Gestapo torture for over a year is impossible to imagine. On November 19, 1944 he was hanged without trial in the Mission Hotel Trondheim13. The Nazis failed to obtain any information from him. King Haakon VII posthumously awarded Pevik the Norwegian War Medal for his “courage and resolution.”

Odd Sørli returned from Stockholm shortly after the failed assassination attempt. He was not happy with the news of the contact between Pevik and EGO – and even less happy when he heard that the radio station had been used as a hospital. In Sørli’s opinion, Ivar Grande, Rinnan’s second in command, was just as dangerous as his boss. Sørli and EGO made two separate assassination attempts on Ivar Grande but neither was successful. Rinnan himself always claimed that he led a “charmed life.” Certainly his network of negative contacts, co-operating with the Gestapo, infiltrated and destroyed several Milorg groups so it seemed only a question of time before they reached the inner core of the ‘Lark’ organisation.

End of Lark Blue

In this tense situation, security at the radio station was strengthened, the name changed from Lark Blue to Lark Green, and a more sophisticated code system activated. London ordered EGO to find another radio operator so he could go to Kristiansund to assist in creating a military organisation there.

After only a short time in Trondheim, Odd Sørli was called to Stockholm to report on the situation. The following day the wife of Odd’s landlord told EGO that her husband had been arrested that very morning – suspected of having a radio in the house. EGO reported this to London but was not particularly worried. Two days later, however, he went to visit the Sødahl family, (Odd’s parents-in-law). He rang the doorbell but instead of a friendly welcome, two uniformed policemen faced him. At the same time he heard Mrs Sødahl voice cry out: “We are all arrested.” EGO spun around and raced down the street – luckily, without being chased or shot.

He reported this latest incident and two days later received the order to close down the station and make his way to Sweden. With Lark Green disbanded, Leif Wiger and Jens Beer took over the Milorg organisation and on October 29 EGO left Trondheim. In December, the Gestapo arrested Leif Wiger, Jens and Martin Beer and several other leaders. Other Milorg men escaped to Sweden. Once again Trondheim was isolated and the organisation torn apart.

The events described in Durham occur concomitantly with those in the previous and following segments.

Trondheim July 1943

Two hours before dawn on the 10th July 1943, American and British troops landed in Italy. The opening of the southern front, Operation Husky, shattered all hopes of an allied invasion of Norway.

In Trondheim, Linge Company agent Erik Gjems-Onstad reflected that all the work of bringing in supplies, establishing depots, and organizing resistance had been wasted. He felt depressed, even though his own operation – Lark, with its radio and courier communication network with England and Stockholm – remained viable. It was in this mood that he saw a Nazi propaganda poster and began to think of other ways to weaken and harass the German forces. What about the negative propaganda used by the Gestapo, would it work against them? With a rough sketch and a text remembered from earlier years, when Germany really was all-conquering, he designed a simple poster:

Germany Victorious on all Fronts.- Join Germany’s victorious progress. Support the NS. Heil og Seil – Quisling. In the background was a large V.

With a covering note he sent this suggestion to Stockholm – and forgot about it.

Stockholm

In December 1943 he was in Stockholm himself. A British major showed him a glossy poster with the “Victorious on all Fronts”- text. “That’s my idea” was Gjems-Onstad’s reaction.

The major offered no argument and added, “How would you like to get involved with psychological warfare?”

“So that’s what it’s called” thought EGO as he quickly accepted the offer. He spent the next month being trained by specialists from Britain in the new arts of psychological-warfare and “black propaganda” (false information). After satisfying his tutors he prepared to return to Norway with unusual, and unusually specific, orders:

1. Undermine the fighting spirit of German soldiers.

2. Increase the number of deserters.

3. Attempt to foster rebellion amongst German soldiers.

Durham was the code name assigned to the new operation. From the start it was important that this operation be kept completely separate from Milorg. After the assassination attempt on Henry Rinnan in October 1943, most of the Milorg leaders in Trøndelag had been arrested or had escaped to Sweden. Gjems-Onstad’s boss, Odd Sørli, had been in London to report on the situation. Now he was in Stockholm with orders for Gjems-Onstad to continue his wireless duties and Milorg responsibilities in addition to the start up of Durham “I would have enough on my plate” was Gjems-Onstad’s laconic comment.

He would not be alone: 2nd Lr.. Ingebrigt Gausland, subsequently a Linge colleague, and Harald Larson, an experienced courier, completed the team. Both were seasoned resistance veterans and Larson had unusually good local knowledge and connections. On March 27 1944 the three left Stockholm.

To Norway

The first part of their journey was easy – train to the north and a short taxi-ride towards the border. From here they were on their own – with provisions for one week, weapons, hand-grenades, 50 kilos of propaganda material in their back-packs – and skis on their feet. Like many similar treks by similar men on similar missions their journey was strenuous, exhausting, and dangerous. The unexpected happened: A late-season snow storm, the cabin where they were to take their first shelter was occupied by a border patrol, and their contact in Trøndelag had been forced to flee to Sweden. Finally, however, with their rather special baggage, they reached Steinkjer on April 3 where Larsen contacted men from his earlier visits and introduced them to Gjems-Onstad. Gausland continued to Trondheim to prepare the stage for the next phase of Milorg’s activities in Trondelag.

New men in Trondheim

Gjems-Onstad didn’t know many people in Trondheim, but by the time he arrived in there on April 6 Gausland had already arranged safe houses and a reliable source of food. Gausland recommended Magne Nordnes, as leader of the new venture. He worked at the Norwegian Institute of Technology (NTH) and was a lieutenant in the army reserve. Nordnes was eager to be given a mission even though, at first, he thought the psychological warfare scheme sounded highly implausible. Architect Ivar Aukrust and Per Lingås joined the team and within two months they had built up a distribution network of 50 men. By the end of 1944, up to a hundred and thirty men were actively working to undermine the morale of German soldiers in Trøndelag.

Most of the material had to be brought from Sweden by couriers. The route taken by Gjems-Onstad and his companions was far too strenuous but Nordnes had another alternative. The Swedish customs officer at Skalstugan supported Norway’s cause and customs officer Bjørn Rygh at Sul, was a friend of Nordnes. Smuggling along the ancient King’s Road between the two stations was soon in full swing. Although German border patrols were billeted in the home of the Rygh family at Sul, the smugglers and the enemy never collided. This was because the BBC sent radio messages the day before the courier was to arrive, and a confirmation message on the day of arrival. A gate leading to the house was left open if the coast was clear.

The German Freedom Party

One of the basic ideas behind psychological warfare was that the propaganda should not appear to be from the allies but from a German resistance movement.

Deutsche Freiheitspartei Drontheim, ( DFP – The German Freedom Party Trondheim) was apparently one of these resistance organizations – but it was completely unknown in Germany. In fact it was simply a product of EGO’s fertile imagination. Its official newspaper, DFP, was an A4 sheet folded to fit, or to be slipped easily, into a pocket. Its writers and printers were Norwegian but their German was impeccable. The first issue was 30/1944 – nobody remembered having seen issues 1 to 29! One of its slogans was “Those who don’t shoot don’t get shot.”

Deutsche Freiheitspartei Drontheim, ( DFP – The German Freedom Party Trondheim) was apparently one of these resistance organizations – but it was completely unknown in Germany. In fact it was simply a product of EGO’s fertile imagination. Its official newspaper, DFP, was an A4 sheet folded to fit, or to be slipped easily, into a pocket. Its writers and printers were Norwegian but their German was impeccable. The first issue was 30/1944 – nobody remembered having seen issues 1 to 29! One of its slogans was “Those who don’t shoot don’t get shot.”

About 1500 copies of DFP came out regularly during the autumn, winter, and spring 1944-1945. The contents comprised a heady mixture of international politics and local news. Rumours and gossip about German military and civilians were popular – but difficult to obtain. One important source was the railway station where two of Durham’s men, Malmo and Smith, had a key contact. Gjems-Onstad tells of a burglary at a German officer’s quarters and a week-end trip to a cabin with German airmen and German women – “…to gather gossip and general information for the newspaper.” Other sources, police, public servants, and foreign workers gave worthwhile contributions but nothing could beat native Norwegian invention and imagination.

The German Freedom Party had other ambitions – offering its members a better life-style was one of them. A brochure printed in Stockholm painted a tempting picture:

The German Freedom Party

Trondheim Group

Attention: The German Freedom Party Speaks.

Germany has lost the war!

In the east, the Russians, in the west, the Anglo-Americans – press invincibly onwards.

Those who continue to fight only prolong the agony of the German people and must eventually bear full responsibility. Do not end up buried in the mass-graves on the western front. Do not spend another dark and cold winter in a forsaken outpost in the far north. NO, join the German Freedom Party!! Or – escape from Trondheim to Sweden!

In Sweden there is no black-out – in Sweden, freedom and human dignity await, – in Sweden one can work for… The German Freedom Party.

Controversy

One of the most controversial pamphlets issued by the GFP was a comprehensive list of the various routes to Sweden: …From here the road to Sweden, the road to freedom, is short. If you, comrade, want to take this chance, then follow our advice on the following pages….

The reaction to this brochure in Stockholm was violent: “What do you mean by printing a list of escape routes and distributing thousands of copies, some of which most certainly will end up in the hands of the Gestapo?” Gjems-Onstad took out a map and asked his angry accusers to point out the routes from Trondheim to Sweden. It didn’t take long, the routes were obvious, and a closer examination of the brochure proved that the contents revealed no secrets.

The icing on the cake of desertion for German soldiers was the DFP’s Border Pass. In German on one side and Swedish on the other, the card, addressed, To our brother Swedish authorities, identified the holder as a German soldier who wished to desert and asked for help and guidance.

Whether or not these various subterfuges succeeded was not easily confirmed. A Swedish border guard once told Gjems-Onstad that he was completely surprised and hardly knew what to do when a German gave the card to him – but he did help the man on his way.

Whether or not these various subterfuges succeeded was not easily confirmed. A Swedish border guard once told Gjems-Onstad that he was completely surprised and hardly knew what to do when a German gave the card to him – but he did help the man on his way.

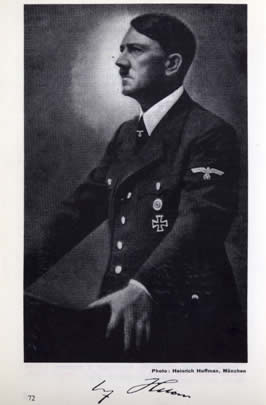

The Naked Truth was a card with a photo of a partially clad woman on one side and a caricature of Adolf Hitler on the other. The partially clad woman would raise no eyebrows today but in those days the photo was considered almost pornographic. The idea was to spread the card amongst German soldiers who would naturally want to keep the “pin-up”. If they were found with the card in their possession the caricature would get them into serious trouble.

Later, The Naked Truth was expanded into a 16 page brochure, with even more ‘revealing’ photos, that was extremely popular – perhaps especially amongst the distributors. (Thirty years after the war, this brochure was the subject of much criticism in the Norwegian Press.)

Letters

In a separate category were hundreds of letters that encouraged German soldiers to desert. Opening with, “A loving thought from home” the letters continued: “If you decide to desert you will need papers. Without them you are lost. With the correct documents there is no risk. Enclosed are the 4 most important: Travel requisition, rail ticket, ration-card, leave permit…” A full explanation of each document followed and included no less than 25 possible ‘reasons’ for the journey. A follow-up to these letters was the field-post letter describing, in glowing terms, the situation of deserters in neutral countries like Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain. The recurring theme of these false letters was: not one person has been returned and the final encouragement: Thousands have already done it. Thousands have dared to take that one, short step from war to peace.

Black and White

Not all propaganda was false, or ‘black,’ as it was called. ‘White’ propaganda came from reliable, known sources. The origin of ‘Grey’ propaganda was suspect, unknown, and unreliable. One of Durham’s basic principles was that ‘black’ and ‘grey’ material must not be allowed to fall into Norwegian hands. This would be wasted effort – and it could be dangerous if good Norwegians began to show the material and talk about it amongst themselves – Trondheim was a fertile ground for informers. Discipline in Durham’s ranks held firm – few Norwegians got to hear about these campaigns.

There are almost fifty examples, with drawings and texts, of the various posters and brochures in the pages of Gjems-Onstad’s book Durham – with headlines such as:

• The Frontline wants Peace!

• Germany Wake-up!

• End Hitler’s War!

• When a Government leads a country to ruin, not only is it a right, but it is a duty for every citizen to rebel. (A quotation from Hitler’s Mein Kampf.)

• The Naked Truth!

All the posters, flyers, and brochures were directed at one or another of the three objectives in the orders issued in Stockholm. A whole series of brochures, not mentioned above, addressed the question of illness: the military suspicion of, which illness to choose, how to induce symptoms, how to simulate an illness, how to convince a doctor that you really did not want to be sick, and how to make it easy for the doctor to believe you. Foot sop, throat infections, serious digestive problems, back pains, loss of concentration, and jaundice were among the “recommended ‘favourites’. The effect of these brochures was impossible to measure, but they were distributed with great enthusiasm. A couple of years after the war a doctor telephoned Gjems-Onstad and told him that the “recipes,”…were so authentic that they remained completely convincing.”

Radio

While Gjems-Onstad, Nordnes and their men were fooling the Germans, the British were misleading (a nicer word), the Norwegians. The greatest morale booster for Norwegians was the BBC broadcasts from London. It was generally thought that the broadcasts, on the 29.8 meter band, were from Den Norske Frihetssenderen, (The Norwegian Freedom Transmitter,) an illegal, mobile, radio transmitter that operated somewhere in Norway. The Gestapo searched in vain for this transmitter. Day after day, month after month, the messages reached Norwegian receivers that were hidden in loft, cellar, outhouse, and wood-pile. In fact, the Freedom Transmitter didn’t exist – it was part of the British black propaganda towards Norway. The station was at the BBC London and the inimitable and beloved voice was an unidentified Norwegian. Throughout the war, and long after – even after his death – ‘the voice’ remained anonymous. Gjems-Onstad is sure it was that of Henning Koefoed, who, after the war, became a director in Aftenposten. Whoever it was, his broadcasts – though often pitted with propaganda – helped maintain the morale, the hope and the determination of his secret audience.

Most Norwegians, however, were unable to listen to the anonymous voice. The Germans had confiscated all radios (except those belonging to NS members), in August 1941. Newspapers were mostly in the hands of Nazi sympathisers and any editor who deviated from the pro-German line was promptly replaced or punished. This otherwise barren media landscape provided fertile soil for rumours, not all of which were spontaneous or innocent. On the contrary, Gjems-Onstad sometimes got orders from London to ‘plant’ a certain story – a story that would be similarly ‘planted’ in other parts of Europe – thus increasing its credibility. Even Gjems-Onstad’s own colleagues didn’t know that the stories were false. Apart from those started in London, most of the rumours were products of local imaginations about German setbacks, weaknesses, and losses. Rumour-mongering was not an allied invention – Nazi leaders used false information to further their aims throughout their rise to power in Germany and during their ‘blitzkrieg’ in Europe. Gjems-Onstad believes that one of the most successful ‘rumours’ ever, that British aircraft would bomb Oslo, was started by German military leaders on April 9th 1940. The rumour worked, on April 10th, later called ‘Panic day’, the roads out of Oslo were jammed with people heading for the ‘safety’ of the countryside.

In Trøndelag, 1944, rumours were one of several minor activities that, collectively, were a constant irritant to the German occupiers. The men of Durham had little choice: they had no access to weapons, heavy equipment, or explosives. Everything they needed still had to be carried by couriers from Sweden or produced locally. Little wonder then, that with the lack of material they had to resort to the unusual – not to say macabre.

Unusual methods

Stink-bombs, for example – but how could such a simple device help the war effort? Imagine a cinema in Trondheim: half the seats are reserved for Germans and their acolytes, the rest are for Norwegians who ignore the injunction of the Home Front to boycott cinemas. As the film begins, someone steps or sits on one of the small, glass globes that Durham’s men have planted. Almost immediately an indescribable stink begins to spread around the seats. The audience rushes to the exits and a tear-gas canister explodes in the foyer causing further confusion. Within a few minutes the cinema is empty. The street outside is filled with gasping, spluttering, teary-eyed people. Military traffic through Trondheim was particularly heavy so puncturing car and truck tyres with specially made, sharp-edged triangles became an effective irritant. But perhaps the most exotic examples were the contraceptives imported from Sweden. Perfectly normal to look at, but invisibly lined with a virulent itching powder, the effects can only be imagined. Certainly nobody in Durham was ever persuaded to test this particular preventative.

Towards the end of the war petrol became increasingly critical for the German forces throughout Europe. The Home Front leadership gave the go ahead for the destruction of petrol supplies in any way possible. In Oslo, Milorg ‘arranged’ many spectacular explosive actions against depots and tankers. Durham, however, with almost no dynamite had to restrict their actions to theft and contamination; they added sugar or saltwater to petrol containers. Even these efforts had to be discontinued when the Germans warned of reprisals if petrol-related sabotage continued.

In many parts of the country Resistance groups were disrupting traffic by blowing up railway lines, but in Trondheim simpler methods had to be found. One afternoon, in the central police station and the central railway station, telephones rang and a mysterious voice said:

Listen carefully,

Specially trained saboteurs have placed charges that will blow up the Central Station. The explosions will take place in 10 minutes.

This warning is given in order to save lives of civilian passengers and railway employees.

The effect was immediate: the station was evacuated and all traffic stopped for several hours. In the hope that this ruse could be used again, the following message was sent next day:

Listen carefully.

Yesterday’s warning of sabotage against the Central Station was not a propaganda hoax, but because of certain circumstances we were unable to carry out the action as planned.

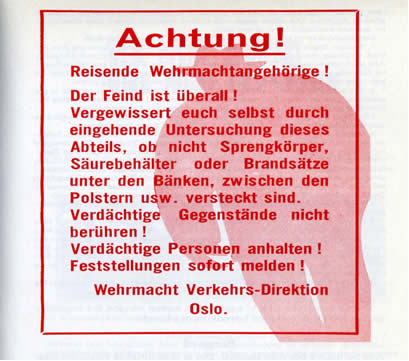

A more subtle action, with a more sustained effect, was the poster purportedly issued by the German Military Railway Management, which read:

Warning

German Military travellers: The enemy is everywhere. Protect yourselves by personally searching this carriage for hidden explosives, acid-containers, or incendiary-bombs.

German Military travellers: The enemy is everywhere. Protect yourselves by personally searching this carriage for hidden explosives, acid-containers, or incendiary-bombs.

Do not touch suspicious objects. Arrest any suspicious persons. Report any finds.

Fifteen hundred copies of this poster were distributed throughout Trøndelag and there is little doubt that its effect was to increase the German soldier’s uncertainty and decrease his morale.

The fall of Hitler’s popularity during 1943-1944 gave rise to a cruel propaganda ploy. German soldiers were offered the chance to earn a signed photograph of “Der F?hrer” if they excelled in battle, preferably by being wounded. If killed, the photograph would go to their next of kin. The “offer” detailed the gruesome conditions on the Eastern front and listed the divisions that were soon to be sent there.

Hitler was also the subject of a whole series of tracts that described a morale-weakening picture of the man, and of the conditions in Germany:

What’s really happening in Germany?

What’s really happening in Germany?

Houses – window-less, Bread-box – bread-less, War – meaningless – and 48 other similar humorous definitions.

If the German people should collapse under the current burdens – I wouldn’t shed a tear – they deserve their fate. (Adolf Hitler)

Prolonging Hitler’s war means more air-raids, destruction of our industries and endless unemployment.

Comrades: Don’t mourn for Hitler. Even if we lose everything there will always be a big plane or a big submarine that can take him to Japan or Argentina. Take courage. The F?hrer will be saved.

Here can you check to see if your home has been damaged …if your home is damaged by enemy air-raids you are entitled to an immediate 10 days, in exceptional cases, 20 days, leave.

Attached was an alphabetical list of streets that had been bombed in major German cities.

Organisation

The Durham organisation worked systematically and thoroughly. Their activities were carefully catalogued and regular reports sent to Trondheim. A typical report: Manpower – 51 men.

Geographic area covered – streets, town districts etc.

Material distributed – how many of which article.

How the distribution took place, any incidents and where they occurred.

Ideas, special operations – stink-bomb attack appear in this report. Material on hand – how many of each article.

A list of German camps, meeting places and residences – 98 in this particular report.

According to Gjems-Onstad there were few illegal newspapers in Trondheim and none with any regularity or wide coverage during 1943-4. Although propaganda and information directed to Norwegians was outside Durham’s scope, Gjems-Onstad felt responsible for the situation and on November 27 1944 he wrote to Stockholm.

After explaining the situation in Trondheim and giving several examples of poor distribution of information, misunderstood information, and mistrust of information, Gjems-Onstad explained:

The reason that I take up this subject at all is not because individual ‘jøssinger 14’ lack exciting reading material, but because I have registered a need for professional Norwegian propaganda in this area. The lack is almost total and the demand inexhaustible.

He than described how the local population was becoming more and more distanced from the realities of the conflict because they had access only to the Nazi-controlled press and unconfirmed rumours:

The less they hear from abroad, the more they immerse themselves in their own problems. They think of food, clothes, the cold, the dark, evacuation, Germans…all in their own way…when someone is arrested by the Gestapo they say: “He was taken but he had done nothing.”

While admitting that he could be criticised for his views by others who claimed to know the situation, and that he had no monopoly on infallibility, Gjems-Onstad nevertheless closed with an undeniable truth:

Spreading well-founded propaganda and news about conditions abroad will have an infinitely positive effect on the cooperation between ‘ home’ and ‘abroad’ fronts after the war.

He expected a critical response but the reaction in both London and Stockholm was extremely positive. The report was considered useful and valuable.

But the decisive point was negative for Gjems-Onstad, the message was clear: Hands-off. You have too much to do and are too exposed. Be careful!

He interpreted this as saying that the leaders and men in Durham were to have nothing to do with Norwegian propaganda – and he supported this whole heartedly. Other actors must play their part and a close contact, Anne Øverås, took the lead. She recruited journalist Per Opøien and a book-dealer Rolf Rydling. Together they produced the illegal newspaper ‘FOR FRIHETEN¨’ (For Freedom). The first issue came out just before Christmas 1944 and others followed regularly until the end of the war.

‘FOR FRIHETEN’ brought another positive reaction from Stockholm. Sørli wrote that that they were pleasantly surprised and extremely satisfied with the contents. He even promised that the Stockholm office would pay a fair share of the expenses!

‘FOR FRIHETEN’ brought another positive reaction from Stockholm. Sørli wrote that that they were pleasantly surprised and extremely satisfied with the contents. He even promised that the Stockholm office would pay a fair share of the expenses!

The attitude of the Norwegian authorities in London and the Home Front leadership in Oslo seemed to have become more positive towards Durham.

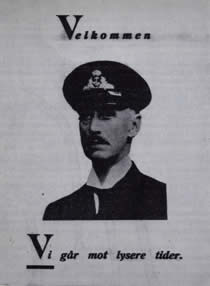

On August 3 1944, King Haakon’s birthday, a supply of 1000 posters bearing a photograph of King Haakon arrived in Trondheim. A further 5000 came on October 12. Some of these were put up on New Year’s Eve, and the rest during January and February. The text, Welcome – We go toward a brighter future, was certainly on target.

With the New Year, and the increasing signs of Germany’s defeat, sabotage again became an important option – especially against railways. What did the civilian population think about sabotage considering the risk to Norwegian lives? Durham started an inquiry in January by asking the following questions:

• Are you for or against sabotage organised by the High Command against important targets if these attacks result in loss of Norwegian lives and property or hostage taking?

• What is your opinion about sabotage against railways?

• What is your opinion about sabotage against troop transports where Norwegian hostages could be killed in the action?

Statistics from the inquiry were laid out in great detail. Only 67 people were interviewed so the basis for the poll, at least in the light of modern opinion-poll knowledge, was far too small to be significant. In any event: “The result was not very encouraging since a majority was against sabotage…”

Towards the end

By the end of the war the Durham organisation had grown to 140 men and women. The leaders recruited by Gjems-Onstad, Nordnes, Aukrust and Lingås, were still in charge as were all but one of their group-leaders. This stability is quite remarkable considering that Rinnan and his gang of informers and negative contacts had caused havoc with most organised resistance in Trøndelag. The Gestapo arrested Otto Lyng, one of the group leaders, in May ’44, but they released him without realising his importance. Two others, Finn Hals and Gunnar Tennebø, were caught pasting up posters in the centre of Trondheim. At Gestapo Headquarters in the Mission Hotel the infamous torturer Ivar Grande was waiting. Tennebø and Grande had been in the same athletic club before the war. This must have had an effect on Grande because after 10 days the Durham men were sent to a nearby prison without being tortured. In August the Gestapo caught Torleif Rognes in the centre of Trondheim with a large supply of propaganda material. Under interrogation he was tortured by Gestapo boss Flesch but refused to give any information. A couple of days later, Claus Pedersen was arrested. At first this arrest was thought to be a result of the interrogation of Rognes. Later it was discovered that Pedersen had asked a friend for help in finding a safe-house to prepare for his escape to Sweden. His friend had contacted another “friend” – who turned out to be one of Rinnan’s negative contacts. This was the closest that Rinnen and his gang ever got to Durham.

How much luck and how much initiative could be involved in these arrests can be discerned in the continuing story of Otto Lyng. After his release he laid low for a while and then continued his activities. One day he happened to be at the Cathedral School when two truckloads of German soldiers and Gestapo agents surrounded the building. One of them asked where the 5th class was located. Otto Lyng replied that there were several “5th Classes…who were they looking for?” “Otto Lyng” was the answer, so the self-same Lyng led the way. When they arrived, Lyng walked into the classroom with the Germans and then calmly walked out again. A few days later he was safely among friends in Stockholm.

While Durham’s propaganda work progressed positively, the task of building up the Milorg organisation in Trondheim stagnated. In November, Gjems-Onstad sent a message to London reporting that the shattered groups in Trondheim were not worth much and that it was difficult to organise new, independent Milorg groups. “Why not merge these groups into other, existing, organisations? …I believe it would be advisable to expand Durham’s tasks to include weapon instruction…”The answer was short and to the point “Until further notice, Durham must not exceed its current mandate.”In one way this was positive: London’s decision to maintain the largest and most effective part of the home forces in Trøndelag “only” for psychological warfare meant that they valued the work most highly. For Gjems-Onstad, however, the situation was frustrating.

Things changed as the end of the war gradually approached. Operation “Polar Bear II” arrived in Trondheim under Capt. Leif Hauge. He needed men to help protect the harbour installations against possible German destruction. On March 2nd Gjems-Onstad sent a new message to London: Presume Durham’s present task ends with invasion or capitulation. Polar Bear II needs large number and suggests collaboration. The reply came six days later:

Important: Durham to cease propaganda work which is now considered of secondary importance. Agree following allocation of Durham personnel: For rat work 15up to 10 men, for Polar Bear up to 50 men – further allocation will probably be essential later. Congratulations to all personnel on most effective work in past.

Final Report

At the end of March he delivered his final report in Stockholm. He reviewed Durham’s work, noted the weaknesses and strengths, named the leaders, and gave top marks to them and to the other men and women he knew personally. He also gave a final accounting of the material distributed, listing each piece separately. The final totals were:

Posters: 257,450

Brochures, etc. 115,320

Though little is known of the effect Durham’s actions had on German morale, there were indications of success. German soldiers were seen escorting prisoners from their own ships through the streets of Trondheim. Many German soldiers were interned in Sweden but it was impossible to obtain detailed information from Swedish authorities after the war. They claimed that 4 different departments had been involved and that it would take a long time before the various records were brought together. But one thing they could say with certainty: At the beginning of the war the number of deserters was negligible. A slight increase occurred in the autumn of ’43 and grew increasingly until the end of the war. This was supported by notices in the Swedish press about the Gestapo searching for missing sailors, and deserters. A Norwegian newspaper reported that in Trondheim the German security police were currently occupied with trying to discover who was responsible for pasting posters on walls during the night.

The Commander in Chief of the German army in Norway sent a Christmas message to his troops in 1944 that contained 5 paragraphs about the benefits and dangers of letters sent to family and friends in Germany.

One of them referred to the “enemy flyers” which “must not be enclosed in letters – doing so would incur the harshest penalties.” Another warned against repeating “meaningless rumours” which, “…most often come from the enemy in a deliberate attempt to create dissatisfaction and uncertainty amongst us.” The message ended: “With pessimism and gloom a war has never yet been won.”

Durham’s leaders and their British colleagues disagreed: their activities may not have won the war, but they made a substantial contribution. As proof, British authorities awarded prestigious medals to many of the leading Durham personnel.

Thamshavn – Linge Co. and Milorg

The Thamshavn railroad at Orkanger, about 40 km south-west of Trondheim, was the first electric railway in Norway. It was built in 1908 to carry ore from the Orkla mines at Meldal in South Trøndelag to the harbour at Orkanger. Pyrite ore was essential to the German munitions industry and disruption of the supply from Norway was a high priority for the Allies. The first attack, Operation Redshank, had destroyed the transformers at Bårdshaug in May 1942. The destruction seriously interrupted both mining and transportation for three months. Petter Deinboll, Per Getz and Thorleif Grong were the Linge men who carried out this successful operation and then returned to England.16

In September Lt. Deinboll was back in Norway again together with Bjørn Pedersen and Olav Sættem. Their target this time was the loading facility at Thamshavn. Because of the longer than normal trip across the North Sea, and local organising difficulties it was January 1943 before they, and their equipment were ready. The first plan had been to destroy the pier but local experts advised against this. Instead they decided to sink a German freighter just before it should leave, fully loaded. On February 21 the five thousand ton Nordfahrt tied up and loading began. Soon after midnight on February 26 a small rowing boat slid out towards the freighter which was still being loaded. Arc-lights lit up the ship and much of the harbour but the ship itself provided a tiny slip of shadow. Expecting to be sighted at any minute, the men fixed the charge and silently rowed away. The Nordfahrt sank, the operation was a success and after an eventful, strenuous and near-fatal period in the winter-decked mountains, all returned safely to England. 17

Though successful, the sinking of the Nordfahrt had no significant effect on the ore supply to Germany. Lt. Deinboll, by now a veteran, was given a new task: to destroy the machinery powering the lifts in the more important mine-shafts or, alternatively, attack the railroad again. Arne Hægstad, Pål Skjærpe, Torfinn Bjørnås, Aasmund Wisløf, Leif Brønn and Odd Nilsen, as second-in-command, comprised the Linge group that was dropped by parachute on October 10th. From their refuge in a primitive cabin, reconnaissance showed them that the Germans fully expected new attacks: extra barbed-wire, flood-lighting and anti-personnel mines revealed this clearly. Deinboll decided to go for the alternative – nine of the fourteen locomotives plying between the various stations. The complicated attack took place in the early hours of October 31 – with impressive results: 5 locomotives destroyed, 1 locomotive damaged so much that it had to be sent to Oslo for repairs, freight-cars and a bogey destroyed, and several buildings damaged. Deinboll was not satisfied; one important locomotive remained capable of maintaining the ore transport. He decided to attempt to destroy this and another locomotive at the same time. The action was set for November 17. As Odd Nilsen was fixing an electric charge to a rail, it exploded – killing him instantly. Deinboll called off the action but Bjørnås, unaware of the accident, destroyed his target as planned.

The group had hoped to remain in the district to make a further attack. However, the intense German attempts to find them, during which they captured Pål Skjærpe, ruled out this possibility and the four remaining saboteurs made their way back to England. 18

After the Germans lost their supply of Sicilian ore in the summer of 1943, the importance of the supply from the Orkla mines increased. The October and November attacks had reduced the flow – but not sufficiently. Arne Hægstad, Torfinn Bjørnås and Aasmund Wisløff were assigned to destroy the remaining locomotives. Code-named Feather II they arrived in Norway on April 21 1944 via Sweden. At about the same time, Eric Gjems-Onstad returned to Trondheim from Stockholm.

In Stockholm, he had been told that Ivar Faye Rode would be a good man to head and re-build Milorg in Trondheim. Rode was not unwilling, but because of his bad experiences with informers and provocateurs he refused to accept the weapons, hand-grenades, poison-pills, and even the propaganda material as positive proof of EGO’s identity. As a last resort, EGO gave Rode a few details of a sabotage action that would occur within 14 days not far from Trondheim. Then he said: “When this happens, you will know that I am whom I say I am – and that our first job together will be to get the three saboteurs safely away.” He was referring to the Feather II operation.

Meanwhile, the Milorg group in Orkla, one of the strongest and most reliable in Trøndelag, made the necessary arrangements and provided information for the three Linge-men. A local farmer built them a concealed hideaway in the woods close to the railroad at a point where they planned to destroy three locomotives and, if possible, a bridge. On May 9 and June 1 1944, respectively, the trains were hi-jacked, the passengers dispersed and the locomotives destroyed. A third action, on June 10 back-fired – the train was heavily guarded and in the exchange of fire, two Germans were shot.19 The shooting resulted in an intensive search for the saboteurs and the Germans offered rewards for their capture.

To create a red-herring, EGO called the police and said that he had seen three men who looked like the fugitives at a place far away from the railway. However, he neglected to collect the reward. His first attempt to arrange a meeting with the Linge men failed, but the men eventually turned up in Trondheim. They were taken care of, rested, and on June 19 1944 they set off on the first leg of their journey by train, truck, and finally on foot to Sweden. The Thameshavn sabotage convinced Ivar Faye Rode of EGO’s identity and thus began another new phase for Milorg in Trondheim

On June 21, EGO travelled to North Trøndelag to contact agents, enlist new recruits, and evaluate Milorg’s strength. At Hegra he visited Rolf and Nils Trøite, old friends who had been steadfast Milorg supporters since 1941. On his return trip, EGO found that Rolf and Nils had been arrested the day after his visit. The arrests had no connection with EGO’s visit; the brothers’ aid to the three Thameshavn saboteurs was the probable cause and during a post-war interrogation, Rinnan said that he had had suspicions about the Trøite brothers as early as 1941.

Stockholm

As previously planned, EGO returned to Stockholm at the end of June 1944. On July 12 he delivered a written report on the status quo in Trondheim and Trøndelag. The report consisted of sections on Durham, Plans for Lark including detailed suggestions and evaluations, sabotage targets, and a list of informers. The report recommended several specific organisational and tactical changes.

These had to be discussed and eventually approved in London – a process that could, and usually did, take time.

These had to be discussed and eventually approved in London – a process that could, and usually did, take time.

Time, in Stockholm, hung heavily on EGO so he, Odd Sørli, and two other men organised a supply trip to the Norwegian border. With their backpacks filled with propaganda material, small-arms, and explosives they travelled north to Torrøn and Gånälven where couriers took their loads into Trøndelag. Back in Stockholm there was still no sign of a response from London so EGO eagerly said “yes” when Kristen Aasen asked him if he would be an instructor on a training course for Norwegian couriers.

Trondheim – new arrests

When the course ended there was still no reaction from London so EGO got permission to return to Trondheim in August. As reinforcements he chose two of the newly trained couriers, radio operator Egil Løkse and Rolf Olsen. In Trondheim, EGO stayed in Herleif Halvorsen’s apartment. Reports from ‘Durham’ and Milorg were positive but both complained of lack of material and supplies. The leaders agreed that couriers and parachute-drops must be increased if the organisations were to become effective.

A few weeks later Halvorsen’s fiancé, Eva Munthe, reported that a man had appeared at her home saying that he was from Stockholm and wished to speak with Leif Knudsen – EGO’ code-name. EGO was suspicious. He wasn’t expecting anyone from Stockholm and, more worrying, although Eva was a ‘contact’ she had nothing to do with mail or couriers from Stockholm. Eva assured them that she hadn’t been followed to Halvorsen’s – she had arranged to meet the man in a park an hour later. They agreed that she should meet the man and give him the address of a certain Knudsen who had left for Sweden some days earlier. Five or six men from Milorg would be watching. When the men arrived, they saw that they were not the only watchers slouching around the park that day. Eva and the man appeared, spoke together briefly, and separated – the man quickly followed by his gang from the park.

It was obviously the beginning of a larger, round-up operation. EGO told Halvorsen that he would leave immediately for Stockholm and take Eva with him if Halvorsen didn’t want to go. Halvorsen chose to stay. That night the Gestapo came to his apartment. He heard them breaking in, he ran up to the loft and dived into the river. His pursuers heard the splash, searchlights lit up the river, and they sent a boat over to the other side. But to no avail – Halvorsen escaped and found cover in a safe-house despite the fact that he had lost his pyjama trousers during his swim.

The radio-operator Egil Løkse was arrested next day when he went to visit Halvorsen. Løkse had no way of explaining his visit. His identity card was as false as his name – he was a radio-operator so the Germans thought they had captured Leif Knudsen. But EGO was safely in Stockholm where he received an urgent signal from London asking him to confirm that Løkse had been arrested. EGO devised a control question that London could send to Løkse. His reply confirmed that he was sending under scrutiny. Løkse, knew none of the Milorg leaders in Trondheim but the Gestapo thought he did and ‘interrogated’ him brutally.

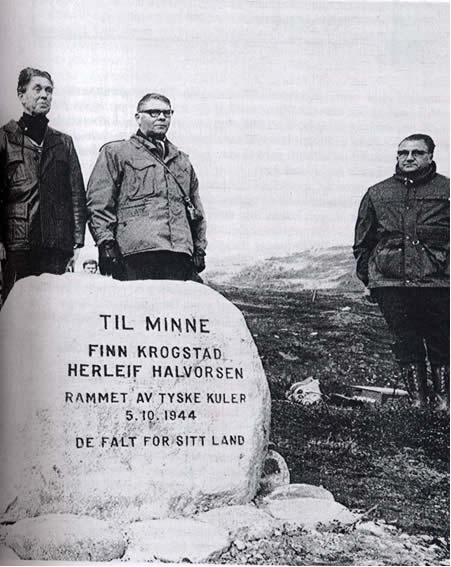

On September 24 the arrest of Ivar Faye Rode and Asbjørn Hørgaard indicated the beginning of another round-up of Milorg leaders. Herleif Halvorsen, Finn Krogstad, and Rolf Leer started off for Sweden with three others.

On September 24 the arrest of Ivar Faye Rode and Asbjørn Hørgaard indicated the beginning of another round-up of Milorg leaders. Herleif Halvorsen, Finn Krogstad, and Rolf Leer started off for Sweden with three others.

On October 5 1944 they were caught unawares by a German patrol not far from the Swedish border, Halvorsen and Krogstad were shot. Krogstad died immediately, Halvorsen, crawled over the border where he died. His body was not found until the following year.

Once again Milorg in Trondheim had been decimated but ‘Durham’ remained intact. A few weeks later a group of men arrived in Stockholm – the remnants of the once sturdy Milorg group in Levanger. Informers and infiltrators had won the day there also.

New Strategy

By October 1944, the focus of the Norwegian resistance had switched to being prepared for when the war in mainland Europe ended. What would the more than 350,000 German soldiers, sailors, and airmen in Norway do? Would their leaders respect orders from a defeated war-machine in Germany? On October 30, EGO once again left Stockholm with instructions to check if it would be possible to rebuild the Milorg organisation in Trondheim, re-establish the Lark radio station, and begin to prepare for defences against German destruction in the event of a warlike withdrawal.

Special troops who were to be deployed in any actual conflicts in Trøndelag were already being trained in Scotland – codenamed Crowfield and Polar Bear 2. EGO’s tasks were to find contacts, arrange drop-zones, provide accommodations, establish communications and, not the least important, gather information about German withdrawal plans. For the latter task, the intelligence expert, ship-broker John Hansen, continued to operate securely in Trondheim. Particularly valuable to the Allies was the detailed information Lark sent concerning troop movements through Trondheim, ship dockings, and convoy movements.

Trondheim – new faces

Otherwise in Trondheim, Anne Øverås, a teacher at the Cathedral School, had already made her mark as messenger and message-drop. Steinar Tønsberg, who worked in the police department, provided her with travel documents so she could roam the county gathering both information and contacts. One of her first contacts, Jenny Johansen, owned a bakery – she supplied bread of all kinds to the Milorg men during that last winter. As many men had been arrested or were in exile abroad, women became more and more active in Trondheim.

Their efforts did not go unnoticed: The British Government awarded the King’s Medal for Courage to Anne Øverås and Jenny Johansen after the war. The Norwegian Government fined Jenny Johansen for selling bread to people without ration cards.

Radio contact with London was established within a couple of days and a ‘secret’ radio link with Stockholm came shortly afterwards. The ‘secret’ was between Odd Sørli and EGO both of whom thought it essential to be in contact. Both also knew that if they asked for the link it would be refused. An extra radio link meant extra traffic and a new radio operator. On November 18 Sørli reported that he had a man, but that he had just finished his training and had no field experience. The man, Fredrick Beichmann, was the son of a Norwegian Army General and this bothered EGO more than his lack of experience. As it turned out, neither needed to have worried, Beichmann did an excellent job as radio operator for Lark.

Reports to Stockholm

On November 22 EGO received the following telegram: “Give a short report on your opinion of ‘Lark’s’ situation.” In his reply the next day he wrote:

Have contact with Heimdal and Orkdal. Orkdal now OK with new leader.

No new arrests, some expansion Heimdal. No joint leadership.

In Trondheim, ‘Durham’ could expand to include weapon-training

New groups like Polar Bear – with specialists from UK highly desirable.

Difficult to find suitable district leaders for Lark

Suggest that either ‘ withdrawn’ district leaders take over, or that districts merge with home forces and Linge-men take charge.

He asked for a prompt, if temporary, reply.

Anne Øverås and two of her friends 20 approached EGO with the idea of starting a new illegal newspaper. They were willing work on this but felt that they had to have ‘official’ backing and a reliable source of news. At that time there was no regular ‘illegal’ news distribution in Trondheim so EGO felt justified in telling them to go ahead. He told Stockholm of the venture and shortly afterwards the first copies of “For Friheten” (For Freedom), were distributed.