the ‘Potato Spy’

In the manuscript that Erling Storrusten has written about his life he describes the geography of southern Norway with particular reference to the valleys. Storrusten’s roots, and those of his wife, Aase-Berit, are firmly embedded in the most majestic of these valleys, Gudbrandsdalen, the main North-South artery in the country. The glacier-sculpted valley is a hard taskmaster, a conduit for surging rivers which bring both life-giving water and death-dealing floods. ‘Dølakar’ – men who come from Gudbrandsdalen – are, according to an old song, the most important in Norway, a merit Storrusten gently disputes. But he has no quarrel with an earlier line: “Dølekar, strong and tough

Strong and tough they had to be, particularly the men and women whose farms, on the west side of the river Logan, included the upper reaches of the steep valley sides, as did Erling and Aase Berit’s ancestors. Here there were no roads and when Erling’s 98 year old great grandmother died in 1940, German aircraft shot at the rowboat carrying the coffin across the river.

Family and Childhood

In 1915 Erling’s father Jacob, obtained a coveted spot as a traffic trainee with the Norwegian National Railway (NSB). He was an apt pupil and in 1917 he started his railway career that took him and his family to many locations, and many interesting challenges, up and down the valley. In those days railway personnel were often the only public servants in the community. Their varied tasks brought them in contact with most of the local inhabitants and Erling’s father became a popular figure. In 1935, after stints at several railway stations, he was promoted to Lillehammer; first as dispatcher, later as freight manager and finally as deputy station manager. It was in this capacity that, in 1942-44, he was able to register, and send to London, lists of German field post offices– information that was of invaluable assistance to the Allies.

The move to Lillehammer was an important step for twelve year old Erling. At his new school he met boys who would become friends for life – in some cases life cut short by war. He joined the boy scouts where he formed friendships and learned practical things, both of which proved helpful later. Home life for Erling and his sister Inger was happy and secure. Their father was a respected figure in the community and his mother spent much time visiting patients at the nearby hospital that served the medical needs of the entire valley. Erling calls her “the hospital angel and many of these patients, who had been neighbours in earlier years, found a warm welcome at the new Storrusten home after they left hospital.

Lillehammer Station

His mother also kept “open house for the children and their friends. Later, during the war, she supported them in their in their ideological and moral opposition to German occupation. Erling writes: “She was, without a doubt, one of the Fatherland’s unsung heroes in those critical times.”

Erling helped his father at the railway station: carrying mail bags, packages of newspapers, and small goods parcels. The conductors called him “Junior station master” and it seemed certain that his future career would be with NSB.

A career in a three lettered transport company it turned out to be – but on wings rather than rails, and SAS rather than NSB.

In high-school it seemed natural for Erling to join a Christian youth group – the only organised activity in the school at that time. He remembers it as an inspiring period, somewhat at odds with the conservative leadership in Oslo but: “…my goodness we had great debates on philosophy, science, politics and attitudes”.

Erling’s home

It was while he was at high school that he first met Aase-Berit, who became his wife in 1950. He used to watch the two year younger student as she walked by his house on the way to school – wearing a red bonnet – a sign of opposition to the German occupation. Then it was just a question of “happening to meet her at the next corner and walking to school with her.”

Remembering the good times at home in Lillehammer with his friends, the friends of his sister, and his always supportive parents, Erling sums up: “All in all we thoroughly enjoyed our life at home and had a good upbringing.”

Invasion

The good times ended abruptly one April day in 1940. Erling writes: “On the evening of April 8th, a hand-written notice reporting that a fleet of German ships had steamed through Danish waters, appeared outside the offices of the local newspaper. Shortly afterwards came the news that a German troopship, “Rio de Janeiro had been sunk outside Lillesand, and that some of the rescued had claimed that they were “…on their way to Bergen.” Erling remembers clearly that he and his friends agreed: “…the Germans will be here tomorrow.”

In Erling’s opinion the Norwegian High Command knew nothing and did nothing until early hours of April 9th. Thirty years later the two officers who exchanged duties at 4 pm on the 8th told him that they did so without having received reports of any special incidents. “Hitler’s attack was a perfect example of well-planned surprise and unbelievable good luck”, is his summing up.

After listening to the radio next morning Erling woke his parents with the news of the German invasion. His father realised that the railway would be an important element in the new situation and left for the station. His mother took things calmly and got the children off to school as usual. But they found that school was closed for the day. The older students were put to work preparing shelters by protecting the basement windows with piles of firewood. School didn’t open again that spring and grades for the final exam of Erling’s graduating class were based the results of previous tests. This arrangement had been planned by the Education Department earlier in the year – a department: “…much better prepared for war than Halvdan Koht’s ‘farsighted’ Foreign Department and Commanding General Laake who, on the morning of April 9, had to leave his command in order to go home for his uniform.” (sic!) On the other hand, he writes: “We should be thankful for the few clear heads that morning: C.J.Hambro, Colonel Eriksen, and Capt. Welding Olsen in his light craft ‘Pol III’ patrolling the outer Oslofjord.”[1]

Storrusten apologises for his crass personal characterizations but does not rule out further outbursts because; “I become so furious both with Hitler and Koht that reasoned writing is impossible (…) April 9th 1940 is the bitterest day in my life.”

The next day Erling’s scout troop was ordered to gather at the railway station in the afternoon to meet the arrival of the train from Oslo. By now they knew that the Germans had taken Kristiansand, Egersund, Stavanger, Bergen, Trondheim, and Narvik. They were unsure about Oslo. While they waited for the train, a heavy truck, loaded with an impressive anti-aircraft cannon, pulled up in front of the station. An old friend from high school, now in uniform, sat astride the weapon and waved to his friends. “This was my only encouraging experience on that black day.” is Erling’s comment. When the train arrived from Oslo it was practically empty and the chief of police told the boys they could go home. Before the day ended they heard about what Erling called: “The most grotesque example of treason, namely Quisling’s impassioned appeal to all troops and seamen to desist from all resistance to the Germans.

What they didn’t know was that Parliament and Government had already reached Hamar and were sitting in a joint emergency session in the cinema there. The continuation of that story is told elsewhere in this web-site but Erling writes of his experience exactly 50 years later, in 1990, at a large meeting organized by the local college to celebrate the historic event in the same cinema:

Elverum Mandate

“I was invited to speak at the meeting and I criticised the publication of a book, based on German sources and biased in favour of Germany. I presented a list I had compiled of German violence and ‘murder’ during their advance up Gudbrandsdalen – actions that were in breach of the Geneva Convention. Afterwards, after all these years, I enjoyed meeting an XU colleague from Hamar. Less enjoyable was coming face to face with a well-organised group of old Nazis who used their freedom to try to prove that they were not traitors because Norway, in reality, hadn’t been at war with Germany: The King, the Crown Prince and Government had fled to England, the Elverum Mandate was illegal , and Norway had made peace with Germany when she surrendered on June 10.[2]

In the days immediately after April 9th the atmosphere was tense, not only in Lillehammer, but throughout Norway. Rumours were rife, mostly because of the uncertainty surrounding the events in Oslo, the fate of the King and Government and, especially, the question of whether the Allies would come to Norway’s aid.

The order to evacuate women and children from the towns came on April 12 and Erling’s father had his hands full at the railway station. Under ever increasing low-flying reconnaissance flights from German aircraft, Erling’s mother took the two children to relatives in peaceful Tretten, a small town north of Lillehammer. The German hunt for King and Government had, however, intensified; Elverum and Nybergsund had been destroyed by bombs but the prey escaped again and the chase continued ever northwards. Erling remembers seeing the Minister of Defence in the street – Tretten was now in the danger zone. Erling’s mother thought it would be safer to stay with relatives who lived in Fåvang, so they moved again – much against Erling’s wishes. He would rather have stayed with the Red Cross group at Tretten. He writes: “However, as a sixteen year old, I was tied to mother’s apron strings.”

In the next part of his manuscript, Storrussten tells of his experiences in Fåvang as he watched ebb and flow of battle until the main action moved away and everyday life resumed. After a short stay helping his aunt and uncle on their farm he returned to Lillehammar in time to see the Germans marching victoriously through the streets singing “Now we’re on our way to England.

School started again in August and, although the Germans had requisitioned many school buildings, and sent many teachers as forced labourers to Kirkenes, the quality of the teaching didn’t suffer and Erling writes: “Time and again, throughout my life I have thanked my lucky stars for the theoretical groundwork we got at school – in History, Geography, Literature, English, German, and a smattering of French. This allowed me to absorb and understand the world in which I have lived and worked. And I have enjoyed being able to talk and connect with interesting people all over the world. The fellowship between the students in our class was excellent, there were no Nazis…and the bond between teacher and student was strengthened by their opposition to a common enemy.”

In spite of a positive scholastic record Erling had to forgo a university education. The costs were too high for the family and anyhow, the practical challenges of a new growth industry – Air Transport – called.

The foundation of the Resistance Movement

The story continues in Erling’s own words:

There is no doubt in my mind that when the history of the occupation is written, the ideological foundation will emerge to have been its most distinctive feature. It is the civil, and not the military resistance that has truly influenced Norwegian history. The contribution of our merchant seamen was important from a world-wide perspective. Milorg was important as a force against the Germans but also because it gave Ola Nordmann the chance to obtain military training to help drive out the enemy.

The MILITARY victory was won for us by the Soviet Union, the USA, and Great Britain.

The CIVIL, IDEOLOGICAL victory, however, was ours alone.

I understood the importance of this when the Supreme Court resigned in 1940. But what concerned us more was the Nazification of the population that Hitler had ordered Terboven to implement.

We were a true, Aryan, Germanic race and would be the showplace in a Jewish-free, greater Germanic Europe under Hitler’s leadership. If the generals had been allowed to run the occupation without political interference, collisions between the civil population and the occupying powers would not have been so frequent. Hitler’s wild idea of turning us into passive, Germanic, elite with Nazi ideology was the true focal point of our resistance. In this confrontation hundreds of thousands, more or less, were active. Without this confrontation I’m afraid there would have been many more Nazis in Norway.

Athletics was the arena of our first fight against Nazification. The Nazi authorities demanded that Arne Saatvedt, (Later to become a leading member of the Gestapo and after the war, sentenced to death.) should be appointed chairman of the football club “Fremad, After the war I read the correspondence in the possession of my good friend Steinar Aasen, who was chairman at the time. The result was a resounding rejection of the Nazi demands. Similar unsuccessful attempts were made against other athletic clubs and organizations. Finally the Nazis dissolved the old organizations and formed new ones. In response, the ‘old’ organizations arranged well-attended ‘illegal’ sports competitions. The ludicrous Nazi directive of ‘forced participation’ in football matches and other sports competitions strengthened resistance and made us all laugh – something we sorely needed to balance the bad news from the battle fronts at that time.

The attempt to force all teachers into a Nazi ‘Teachers Union’ had more serious consequences. The stakes were higher too: The Nazis demanded that their ideology be an integral part of all teaching. They backed this up with threats of loss of salary and pensions, and the actual deportation of hundreds of teachers to forced labour in Kirkenes. But the answer was a unanimous ‘NO’ from teachers, students, and parents alike. After the war, the teachers’ leader, Kåre Norum, told me how he had organized his members by summoning one representative from each school to meet him separately in Oslo. As they walked the streets together, he brainwashed them with the ‘free’ Union’s viewpoints and arguments so that they could return to their schools well-prepared, but without any compromising documents. Finally the unbelievable happened: At a mass meeting in Oslo, the Nazi’s teachers’ leader, Orvar Sæther, abandoned the whole project with the words: ‘You have ruined everything for us.’ This was a great victory – and proof that resistance paid off. Without any intervention from the military, Terbovens power had been reduced.

The clergy were next in the line of fire. Quisling’s Interior Minister began to interfere in church affairs by forcing a change in the liturgy that included a prayer for ‘King and Family’ and ‘Sons of Israel’. At first the Church appeared to comply but soon made an about-face. The Church Elders wrote a ‘Pastoral Epistle’ which was to be sent to every congregation. Distribution was a problem because the letter had to remain a secret until it was read simultaneously from the pulpits of all churches at High Mass. Sturresten remembers his part in the distribution and the aftermath:

“I had the honour of taking the train, (illegally, without a travel permit,) to Otta. At Øyer, Ringebu, Harpefoss, and Otta stations I gave the letters to railway employees whom I could trust and they delivered them to the local pastor. I took the bus to Follebu and continued on skiis to the church at Gausdal. All went well. Aase-Berit and her parents were in Gausdal for their Easter holiday and they were in the church when the letter was read.

Today it is almost impossible for people to grasp the importance of what happened next: In spite of the economic consequences, the entire clergy resigned. Churches were closed, Bishop Berggrav was confined to a cabin in Asker, and many pastors were sent to Lillehammer to live with private families where they received money and food collected in their respective congregations. The clergy became an active army of ‘jøssinger’,[3] spreading anti-nazi propaganda among the population. Later they were sent to Helgøya where they were easier to control.

Terboven’s planned to put Bishop Berggrav on trial and have him condemned to death. This plan was thwarted when the influential Graf Moltke came to Oslo to meet and talk with his old friend Falkenhorst, (Military Commander in Norway) and Lt. Col. Steltzer, who was, unbeknownst to the Germans, in contact with resistance leaders. The German need to avoid disturbances was the deciding factor. I emphasize this case to illustrate the moral power evidenced by the clergy’s attitude to the German nazification efforts.

One of the few pastors who fell in line with the Germans was appointed to Lillehammer. The poor fellow preached to practically empty pews. The ‘illegal’ pastor, however, gave his well-formulated theological and political sermons to packed houses in the large assembly hall of the local bank.

Again, the examples of athletes, teachers, and pastors show that moral courage is more than a match for military might.

The Illegal Press

The story of the illegal press is a chapter on its own in the history of civil resistance. The regular newspapers and news-bureaus were thoroughly censored, radios forbidden and the cinemas showed only pure propaganda for ‘the new era’. Where could one find ‘free speech? The answer: in the free, illegal press. Many, many men and women were arrested in its cause. Punishments were hard, death often followed. But the price was worth it. Editing, printing (often with evil-smelling chemicals and poor quality machines), packing, and distributing were all important links and all were vulnerable to German control. It is hardly surprising that things went wrong now and then. At home, the highlight of the week was when a man arrived with a package full of ‘newspapers’. The package was given to me to distribute as I liked and I must have been smart enough to pass them on, preferable via several channels.

My last contact with the illegal press was the evening I escaped to Sweden. I was to spend the first night in the cabin where the author Hans Heiberg edited the local illegal newspaper. As he was busily digging his typewriter from the snow he gave me his ‘Sweetheart’ (a British mini-radio) and asked me to listen for any last minute news that should be included in the latest edition. The newspapers of course, contained much propaganda, but, with information folk could trust, poems, and satirical, anti-nazi jokes, they were an important support for the population for more than 4 years. I calculate that in Lillehammar and Gudbrandsdalen alone there were a couple of hundred active distributors. In addition there were those of us who had illegal radios. We passed on news to those we could trust and they passed it on again. I bless every one of the thousands of creased, often soiled new, and not so new, illegal newspapers that circulated before being burnt under close security to ensure that no trace remained.

The Compulsory Labour Service

Another subversive aspect of the ‘new order’, the Compulsory Labour Service (CLS), was especially important for me personally. We knew from ’moles’ in the Nazi administration that those drafted into the service could, in time, be used for more important military purposes than merely digging ditches. I had no intention of joining such a group, putting on a green uniform and possibly being forced into war service for the enemy but it was not easy to convince others of the danger. Many thought that the dangers connected with NOT complying, of being ‘on the run’, were just as great. Due to my position in XU[4] it was arranged that I should get a medical certificate to exempt me from the CLS and when the order came to boycott the CLS I began to recruit my trusted friends into the official Norwegian military resistance movement (Milorg). Some accepted immediately but others wanted to know who the leader was in Lillhammar. To this I replied that they knew him but that I couldn’t tell them his name.

Several of the new recruits did a good job in Milorg but they were raw and lacked experience. One of them broke-down under interrogation and mentioned my name, something he aught not to have done (!) Another was shot when, under torture, had disclosed the location of a hiding place where a German had been killed. Under similar circumstances, the name of a Milorg leader was uncovered and he was later ‘murdered’ at home. Some of those who survived the imprisonment and torture suffered for the rest of their lives from physical and mental problems.

In 1990 I took part in an official meeting and during a break, almost by accident, I met a man who had been a ‘general’ in CLS. I said that it was interesting to meet a man who had been such a bitter opponent during the occupation. He thought that I must have been dumb to believe that the leaders of CLS, who were all ‘good’ Norwegians, would have transferred us to German military service. I asked him who he thought had most power: The German ‘Wehrmacht’ or the insignificant officers in the CLS? I also told him about the document from the Nazi department that outlined the possible changes in the labour services. I asked him to understand that it was impossible for us to believe that he could have guaranteed that we would avoid military service for the Germans. This seemed to give him food for thought and that strengthened my convictions that we had been right to boycott the CLS. But this is highly hypothetical – the actions of the Hird and the police, both civil and military, against their defenceless countrymen are real proof that we were right.

Resistance

Much of my work for Milorg was as a courier for the head of district 23 (D23) which covered the entire Gudbrandsdalen. The district was divided into sections: 231 for Lillehammer, Fåberg, Gausdal, and Øyer, and 232 from Tretten to Ringebu. The section leader in 232 bred foxes on a farm high up in the mountains. I can’t count the number of times I cycled up there with mail and smaller pieces of equipment. On the way north I peddled as if the devil himself chased me. I did have an alibi for my frequent trips because an aunt and uncle lived in Tretten. However, the material I carried was extremely compromising and would have been impossible to explain away. Luckily, I was never stopped. The 30 kilometer northbound trip took only 75 minutes but southbound, I could take it a little easier because there was less risk involved. Late one evening, cycling southbound, I sensed something in front of me. I slowed down and in the light of my bike-lamp I saw four Capercaille: a male and three females, in the middle of the road, pecking at the gravel to help their digestion – a special, peaceful experience in the midst of strife and terror.

In section 232 I restricted my contacts strictly to the section head, the stationmaster, and a woman who was the last link in the escape route from Tretten, via Østerdalen to Sweden. The staff of D 23 in Lillehammer was larger and my contacts here were the heads of communications, engineering, health services, and supplies.

“Section 231 was divided into groups and each group comprised several teams. As courier, I shuttled back and forth with materials to all these and thus was known to more contacts than strict rules of security required. This was unfortunate, especially for me, but what were the alternatives? On my many expeditions again, I was lucky and avoided any kind of control. I continued my impassioned discussions against the Compulsory Labour Service with my friends and others – especially among workers on the railway. This, too, put me at risk but there were no negative consequences.

Being a courier was only one aspect of my work for Milorg and here are two special episodes that I remember well.

In the large, uninhabited woods north of Lillehammar we had built a solid weapon depot with log walls and a floor covered with heather. The cabin was built over a natural depression in the ground. The final touch was a small fir tree with a good clump of earth that we planted on top – the perfect cover. Apart from weapons, this was the home of ‘Snekkeren – our expert radio operator. He was from the UK and maintained regular radio contact with London. I had been sent up to “Snekkeren with a message and while we sat there the radio broke down. We decided that I should take the faulty part down to the radio workshop in Lillehammar so I set off over the marshy woodlands. ‘Snekkeren’ had fixed times for his transmissions. The Germans knew these times and they tried, unsuccessfully, to zero in on the transmitter. Just when a transmission should have been in progress I found myself in wide opening in the woods. Suddenly a Storck aircraft, (a German reconnaissance plane) droned above. I stopped, almost froze, but then waved frantically with both arms. The two men in the cockpit waved back and I thanked my lucky stars that they were not sitting in a helicopter. The damaged part was replaced, I took it back, and ‘Snekkeren’ continued his transmissions, from diverse locations, for many months. He was a good chap.

Our hideout soon became full of equipment dropped by British aircraft Later the hideout was discovered by the Germans from information extracted during the torture of one of our men.

The next episode was more dramatic:

Two of ‘my’ CLS men were apprehended by group from the Gestapo on a country road shortly after an air-drop. One of them was the infamous Arne Saatvedt, who knew the men from their schooldays. Immediately Saatvedt began to beat and torture the men most violently. One of them managed to tolerate the torture – and suffered from it for the rest of his life. The other, finally, broke down and whispered some apparently innocent, but in reality fateful, information. The Germans drove straight down to Otta and to the home of the Milorg section head. He had just received a visit from one of our railway contacts who had delivered a large ‘post package. ’Saatvedt shot the Milorg man to death through the door but the ‘postman’ jumped out of the window, ran away alongside the river, and into hiding. The Germans went through the package in which there were a couple of intelligence letters from me to my contacts. But the letters contained no identifiable sender or recipient – only our ‘aliases’, or organization names. What they did find was a luggage ticket for a dispatch from Lillehammer to Otta. There was no name on this either but by presenting the ticket at the railway station they received a bicycle and this they could trace back to Helleberg’s sports shop in Lillehammer. They raced to Helleberg’s. ‘Who had bought the bicycle?’ An employee who was a Milorg man heard the question and immediately disappeared into the men’s room, out of the window, and over the street to Odd in the radio shop. Odd dropped everything and ran down to the Clothing Factory where his brother, Torleif, section head of 231, worked. They saw the Germans drive into the factory yard. While Odd walked calmly out of a side door, Torleif grabbed his revolver and sped up to the loft where he hid in an air ventilator. Shortly afterwards a German came into the loft with a watchman as hostage. ‘Was ist das?’ he asked. ‘Das ist varmluft’ answered the watchman. The German slammed down the hatch in front of Torleif’s startled eyes. Torleif knew the watchmen and their routines so he waited until the midnight change before banging on the door and being released by a nervous and agitated night watchman.

The brothers had agreed that they should meet at their cabin outside the town. In the meantime I was innocently on my way to Torleif’s home with the ‘post’. I leaned my bike against the steps and climbed up to the door to ring the bell. Just then the daughter in the neighbouring house opened her door and hissed: ‘It’s full of Gestapo in there.’ Back to my bike and as I pushed it through the gate, and was about to mount, a Gestapo car screeched to a halt, two men jumped out and ran towards me, pistols drawn. I thought I was done for but they raced right past me, up the stairs and into the house. I must admit that I was shaking like a leaf as I, as calmly as possible, cycled slowly, yes slowly, up the street before hurtling full speed down the main road.

I went to my father who was at the railway station, told him that something was wrong, and that I would probably have to ‘disappear.’ He than said something that burned deep into my soul and made me realize the depth and importance, of family love: “If I should be taken as a hostage for you, the worst thing you could do to me would be to come out of hiding to get me free.’ He was, I didn’t, and he suffered terribly.

Then I was told to meet Torleif and Odd at their cabin. Torleif gave me a letter for his mother and the task of telling Peder at the factory to remove, piecemeal, all the secret documents he knew about. Peder was a leading member of the Inner Mission and father to several children. In the course of three days, in his briefcase between his thermos and sandwiches, he delivered everything to me. He greeted me by saying: ‘If Torleif gets caught he would be shot immediately.’ He wasn’t far from the truth.

The next task was to get someone to take over Section 231. I asked one chap I knew, an adult, experienced man, but almost tearfully he said that he simply didn’t have the nerves and that, anyhow, he was to be married shortly. The offer then went to the area head in Nordre Ål who took the job but who shortly afterwards had to flee to Sweden with the Gestapo on his heels.

One night I guided our head of supplies, Tønnesen, over ice-crusted snow in majestic moonlight to the farm where Torleif and Odd were hiding. The next time we met was in the Hotel Omnia, Stockholm.

XU- The Secret Intelligence Organization.

One day early in 1944 Eivind Esp, Inspector of Schools and leader of ‘Sivorg’[5] wished to speak to me. He knew us all from our time at senior high school. He told me that it had been decided to release me from my position in Milorg and transfer me to Military Intelligence. The leader for Lillehammer and Gudbrandsdalen was reduced by illness and needed a young, fearless assistant. The leader’s organizational name was Dale-Gudbrand. He was a prominent athlete and a well-known vocalist. Most important of all: he was employed in the council Building Engineers office where he had access to all maps and the opportunity to reproduce them.

I had to learn all about codes, coding and decoding – using Hitler’s masterpiece, ‘Mein Kampf’ – and other equipment, including secret (invisible) ink and a typewriter. Most important of all was a list of the agents, both in town and in the valley, with their aliases and passwords. I had to dig a hole in the garden lawn, bury a box containing all this equipment and replace the turf. The box must never fall into the hands of the enemy.

My first mission was in connection with rail transport. Two trackmen, on separate shifts, reported the number of trains, the number of soldiers, artillery, tanks, etc. that passed through Lillehammer. Nobody knew that Dale-Gudbrand also received information about the German field post numbers from my father. This was routine but one day one of the trackmen telephoned, saying that he wanted to speak to me – urgently.

In the station a heavily guarded train stood at the northbound platform. I bought a ticket to Tretten (within the 30 kilometer limit), and walked along the platform after asking in a loud voice where the passenger carriage was. A Nazi guard followed me towards the front of the train but I was able to study the tarpaulin-covered flatbeds. Afterwards the trackman and I agreed that the objects on the train must have been one-man submarines, probably intended for use against the Murmansk convoys. He reported his findings in the routine way but later, behind a closed door he was interviewed by a technical expert. The sketch that accompanied the reports was graphic enough. The torpedoes never arrived at their destination.

I visited Dale-Gudbrand one day in 1944 and found that he had had a stroke and was in hospital. The doctor-in-charge had arranged for a private room and on my first visit D-G told me to advise one of his colleagues. This unmarried man, also a prominent athlete, was deeply involved in our activities and was reckoned to be Dale-Gudbrand’s successor. When I told him what had happened, and that he was to take over, he said that he didn’t have the courage to take the job. He resigned on the spot and gave me all his equipment. Dale-Gudbrand, sick as he was, almost jumped out of bed in anger when I told him the news. ‘Now you have to take over’ he shouted. I told him that this would be difficult because I had been drafted into the Labour Service and without a doctor’s certificate to exempt me I would have to go under ground rather than work for the enemy. ‘I will fix that’ said the doctor who stood nearby. He sent me to a TB specialist where I was transformed to a coughing, barking, weakling who looked as though he had seen his last days – totally unfit for Labour Service.

Lillehammer Tourist Hotel (old photo)

Now the tide was turning against the Germans. After their defeat in Finland they retreated into Norway. Gen. Rendulic (known as the ‘fire-starter’ because of the scorched-earth policy decreed by Hitler) was appointed C in C Norway. He moved his entire headquarters to Lillehammer Tourist Hotel and its surrounding forests.

Our mission was to gather information and sketches – something one didn’t learn at school. How could I, newly graduated from senior high school, pry military information from the world’s most professional military power since Napoleon?

The answer was what I later called ‘The Gudbrandsdal Method’ – in other words, the simplest way. My greatest fear was that if I should be caught I would break under torture and inform on my colleagues. Furthermore, if I were caught, too many members of the resistance movement would feel insecure and afraid of being unmasked. Thus I had to find a way to operate that would arouse no suspicion of my being in collaboration with others.

Apart from the hotel building and some requisitioned houses, the new German headquarters had to be built from scratch by slave-labour POWs. The prisoners were constantly hungry. In the evenings they carved or fashioned small articles from the trees and materials they found on the ground. At home we had a small potato patch in the garden. Mother cooked some potatoes, which I put a brown bag and went to find an unguarded opening through the woods into the camp. Once inside, I wandered around, coughing and spluttering, a crumpled brown bag under my arm and a blank, idiotic expression on my face. The German guards scarcely noticed the obviously half-mad youngster who was trying to exchange his potatoes for the small articles the prisoners had made. But all the time I was observing the lay-out of the huts, the bunkers, the bomb-proof command post, and the defences – trying to fix them into my memory. I even managed to stumble up to the officers’ houses and read the names of the occupants on the doors. Of course I couldn’t speak German!

After each tour I wove my way haphazardly through the woods again and, making sure I wasn’t followed, entered the main Post Office in the town square. Upstairs was the Building Engineers’ office where experts positioned my observations on their detailed maps.

The Bank building that housed the Post Office

I and my guardian angel, continued thus for several days. The resulting map showed every single building in the area, the pipeline down to the electricity generator, and of course, all the military installations. We sent the map via our ‘post’ route to the XU office in Stockholm where, months later, I was highly praised and paid double daily allowance as a ‘thank you.’ Reportedly the map was sent to London with a copy to the Swedish Army Staff. After the war a copy turned up in the effects of the XU Leader but it had been so heavily micro-filmed that most of the details had disappeared. I am almost ashamed of the reduced map that appears in’Norges Krig’. I remember the original as being much more impressive.

Dale-Gudbrand had been released from hospital and was at home but in poor shape. One day I came to visit him and found him dead. Our first task was to inform all our contacts and advise them that the new Dale-Gudbrand would take over where the old one left off – with the same address and password. Our man in Dombas was afraid of reprisals. Dombas was a German garrison town so reports from there were important to us. The reports continued to come.

One day a message arrived: “The bear is coming. This was code telling us that an important person from London or Stockholm was on the way. I didn’t know that the person in question was known in the neighbourhood and arranged to meet him at the bridge in Søndre Ål, He was to stay in the ‘safe house’ of a neighbour who was absent.

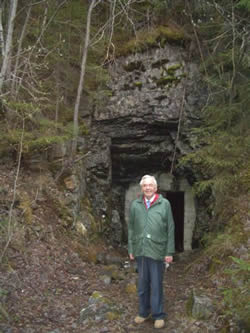

Erling Storrusten in front of his boyhood home.

If the narrow window at the on the right side of the door

was open, he was not to enter.

’The Bear’ turned out to be a man that the whole family knew from Lillehammer. He was accompanied by a radio operator. Because he was so well known in the district we had to find him a new safe house.

The XU staff in Stockholm decided that the perfect replacement for me in Lillehammer would be the son of the owner of the Tourist Hotel. This decision was both smart and timely because things were getting too hot for me.

So hot, in fact, that I dare not sleep at home. Aase-Berit’s parents let me sleep on a sofa in the living room. It had an escape route down to the basement. They thought I was hiding to avoid the ‘Labour Service’ and didn’t know about my resistance activities. Fortunately the Gestapo didn’t know about my friendship with Aase-Berit either.

One evening my sister Inger and I were on our way home from a party. I had intended to pick up a radio and the organization’s cash box at home but I didn’t want to wake up Mother – she was worried enough. I said ‘good night’ to Inger, strolled to my hideaway and slept innocently while a drama unfolded at home.

Earlier that evening a young Norwegian had come to our house and asked for me. He used an alias of one of our men in Milorg. Mother said that she didn’t know where I was but that I might be home later that evening. A couple of hours later the same boy returned, this time with his hands in the air and Gestapo soldiers pointing machine guns at his back. My parents were pushed into chairs in the dining room and left with the ‘prisoner’ while the Germans ransacked the house.

The ‘prisoner’ said that if only he knew where Erling was he could, perhaps, warn him. Father saw through this play-acting and gave a sign to mother who remained silent. When Inger came home one of the Germans knocked her down and threatened her with strangling. But she absolutely denied that she had any idea where I had gone after she parted from me. One of the Gestapo men (previously a YMCA member from Hamar who had been in to scout camp with me), forced her up to my room at gun point where he found my radio and a small roll of kr50 bills. Then he went through a photograph album of mine and ordered Inger to point out my girl-friend. Fortunately, Aase-Brit’s photo hadn’t found its way into my album yet so this trail was cold.

Other photos led them to friends of mine but none of them could give the Gestapo any information. The Gestapo waited all night hoping, in vain, that I would come home.

In the meantime Kiri, who lived in the next house, came home with her boyfriend. Before going in, they went alongside the house to take down some washing. In our house, mother, with the Germens standing threateningly over her, realized that someone was outside so she started coughing violently. Outside, Kiri listened and heard Inger’s voice: ‘I don’t know, I don’t know’. Kiri guessed what had happened. She knew my hideout and was afraid Inger would reveal it under the violent treatment she was getting.

Shortly afterward Aase-Berit’s mother woke me and said that somebody had rung the doorbell. I rushed down to the basement but quickly came up again when it turned out that the caller was Kiri’s boyfriend. Kiri was with him and they told us what had happened. I flung on my clothes over my pyjamas, my rucksack was ready packed, but I had only a pair of thin street shoes to wear. My walking boots were at home.

Escape

With Kiri and friend well in front, to give me a chance to split if any patrols came along, we walked through the dark streets. We headed for a path through the woods but before Kari and friend left me we burned the compromising documents that I had received that day from Dombås.

Then I set off alone towards Sollia where my good friend and compatriot the area leader for Sør Ål lived. I had to take off my shoes because of the deep snow. At Sollia, the house stood alone where the road ended and all was quiet. A light shone from the window and I was afraid the Gestapo had already arrived. After a while I sneaked up to the window and saw that the room was empty – they had simply forgotten to draw the blind. To avoid waking the family I spent the night in my sleeping bag close to the barn and an escape route into the deep woods. Next morning Anna was surprised when she came out to feed the animals and found that she had a visitor.

Aase-Berit and Milorg friend Steinar arrived next morning with my walking boots and a report on the situation. Father had been arrested but otherwise it seemed as though the search for me was an isolated episode resulting from the arrest of the two Labour Service boys. After a couple of meetings we agreed that, because of my courier activities, I had become too great a risk to remain in the district. All my official equipment was handed over to my successor.

Then, in the moonlight outside the house, it was time to say farewell to Aase-Berit. I admired her for her inner-peace, her judgement, and her willingness to continue as ‘girl friend’ for a Milorg member away and on duty. We knew that we might never meet again but we chose to be optimistic and to be happy that the war was obviously coming to a close. Norway needed girls like this! And I needed a girl like this too!

Skiing conditions were good. I was in fairly good condition but since I mostly had to travel at night I slept little – and ate less. The guides[6] were unbelievably selfless and they took great risks. The routine was to give the first guide an envelope containing kr.50 for each leg of the journey. The envelope I handed over contained kr.350.

My route:

From Lillehammer to Mesnalia (Spent the night at Heibergs cabin, described earlier) – Sjusjøen- Birkebeiner trail to Skramstadsetra.

The guide here later told King Olav that he had been given orders to shoot me rather than let me be captured alive – this provoked a headline in the newspaper Dagbladet in April 1995.

At Skramstadsetra the new guide advised that the route was blocked at Ossjøen where two men had been shot. He gave me his Border Permit with a photo that wasn’t so unlike me and made me learn by heart the names and birthdates of his wife, children, parents and grandparents. German patrols often asked such questions and if there was a discrepancy in your answers you could end up in an interrogation room.

At Skramstadsetra the new guide advised that the route was blocked at Ossjøen where two men had been shot. He gave me his Border Permit with a photo that wasn’t so unlike me and made me learn by heart the names and birthdates of his wife, children, parents and grandparents. German patrols often asked such questions and if there was a discrepancy in your answers you could end up in an interrogation room.

A nervous driver took me on the next leg of my journey to Stai. The car had a gas generator on the back but this was camouflage – it had a petrol engine. He assured me that he had checked and confirmed that the Germans were not patrolling the neighbourhood that night. At Koppang a light shone through the window of the Gestapo office where one of my ex-schoolmates worked. The road alongside Mistra had not been cleared so the going was heavy, then down Elvdalen, through Engerneset, and into the forests framing the border. As we approached Pelle Anderrson’s cabin on the Swedish side, my guide lost his way in the dense fog. But, like all good boy scouts, I had a compass in my rucksack, we found the right track, and when we parted the guide was a compass richer for future trips.

Pelle Anderson lived the simple life on his modest mountain farm but he was warm-hearted and generous to his Norwegian friends. Bad weather forced the guide and me to sleep on the floor in front of the fire while Pelle and his wife, Grandfather, several children, and three dogs shared the few remaining square feet of the inner room of the cramped living quarters

Next day Pelle led me eastwards to the road between Særna and Gørdalen. I left my skis with Pelle and began walking, in my white camouflage overall, along the snow-decked road. Before long a military patrol appeared: ‘Halt, where do you come from?’ From Norway I replied. ‘From Norway – without skis?’ was the sceptical response. I showed them my student identity card: ‘Oh yes, student – we’ll write saboteur in our report.’ Thus I became Norwegian refugee number 53000 (or thereabouts), to be registered in Sweden.

Sweden

Gørdal Customs post was a friendly place but the atmosphere had been much more reserved earlier in the war. After being thoroughly searched I was given some food and a sofa in the office to sleep on. The bad weather continued so the trip to Særna was postponed until next day.

The magistrate at Særna wanted to know why I had come to Sweden and I replied that it was because I was wanted by the Gestapo in Norway. ‘But why’ he asked and I replied that it was because I listened to London on my radio and relayed the news to my neighbours. With this in my report I was to be sent by train next day to the central refugee reception at Vingåker, Kjesæter. But first, behind bars, arrested! Still, it was a better alternative to the Gestapo prison Trararo in Lillehammer. How strange, to be free, and yet happy to be in prison, to have food and to be able to sleep.

The refugee senter at Kjesæter was crowded. Columns of refugees from Finnmark came marching in to be welcomed by family and friends. Everybody was waiting for something: interrogation by Swedish or Norwegian representatives, clothes, travel orders, or documentation. I got special treatment: a visa to Stockholm and the address of the XU office in Jongfrugatan. I was told to hurry. In Stockholm, XU feared for the Lillehammer organization because I had reported some arrests a couple of weeks earlier. I calmed them: These arrests were of Milorg members, XU was intact – and it remained so until the end of the war. Then praise for our map and information about its distribution which is described earlier. I worked in the office for a while but was not happy. There was too much talk of money and houses. After the active life in Lillehammer, Stockholm was too static for me.

I lived in the small Hotel Omnia in Kungsgatan together with my old Milorg friends Odd and Torleif and several other refugees. Behind locked doors we worked on our weapons and studied my map in preparation for the time we could return to Lillehammer.

We often had dinner at Berns Restaurant in the evenings – what a difference from the Germanic ‘paradise’ in Norway. But I couldn’t wait to get away from the XU office. One day I discovered that London had seconded some men to jobs in the Air Force. This was for me and I made the necessary applications. In what seemed like no time at all I was sitting in a civil BOAC Lockheed Loadstar bound for Scotland. After about an hour the plane made a turn and an hour later we landed – back at Bromma airport. A Norwegian secret service man had reported that a German fighter had taken off from the airport at Gardermoen because a German spy in the tower at Bromma had radioed our departure and destination. Full speed into the world of spies!

Next day we tried again. I knew none of my fellow passengers except for a Milorg man from Lillehammer and the LO Leader, Konrad Nordal. The windows were blacked out and we were given strict instructions not to show any light. However, I couldn’t resist taking a peep and below, bathed in moon-light, I got a farewell glimpse of Norway. For the remainder of the trip I slept. I awoke to the blinking of runway lights through the darkened windows – we were over Leuchars airport north of Edinburgh.

Perhaps it will be difficult for my descendants to understand the unreal feeling of sitting in a civilian English aircraft, flying over our own country, with German fighter planes chasing us. But now I was about to attain the dream of thousands of Norwegian young people: to be in England and perhaps join the fight against the Germans. For me, this reality had come so quickly, and so unexpectedly, that it was almost unbelievable.

England – Symbol of Freedom

The Scottish police apologised for having to arrest us – since we came from enemy territory – but consoled us by saying we were of the same race with a similar language. One of them pointed to a house and said that in Scots the word was ‘huus’, church – ‘kirke’, etc. After a short interrogation at the police station we boarded the famous ‘Flying Scotsman’, our train to London. We felt strange sitting in a guarded compartment with strict orders against outside contact. We offered to give our seats to some ladies standing in the corridor, but oh, no.

The next day we found ourselves in London at a place called ’Patriotic School’ where we were to go through a security control. Conditions were fairly primitive, there was not much food, and we were surrounded by barbed wire. Suspect Frenchmen had previously been interned here but now it housed a hodge-podge of impatient young Europeans waiting for security checks. I was surprised when many of the Norwegians went through the process quickly and were released – some to join the coastal artillery. Their connection with Milorg or military intelligence had been small and their identities had probably already been checked by the police in Sweden. I was not among them.

For me, the stay here was an endurance test.

Interrogation

The first hurdle was my identity. The interrogators said that they knew me but that they must be convinced that I was not a double agent working for the Germans. They questioned me exhaustively on my escape and on the organization. Where? How? Who? When? I answered openly as far as security considerations allowed but I used exclusively our official aliases. When they demanded real names I refused for the simple reason that it would be a breech of security to allow these names to appear in a report. The men behind the names were still active in enemy territory. And besides, how could the interrogators be sure that there were no enemy spies in the camp? They went so far as to threaten me with imprisonment until I became more co-operative. To this I replied that I would rather stay in prison for the remainder of the war than put my colleagues in danger.

Parallel with these tough sessions on identities, they asked about the military details of the German Headquarters in Lillehammer, the German troops in Gudbrandsdalen and details of rail transport up and down the valley.

At last they must have been convinced of my trustworthiness and I was transferred to the Royal Norwegian Air Force Headquarters in Kingston House, near Hyde Park, in central London.

I got an apartment in Highgate and nobody could possibly imagine my boundless exhilaration as I walked through the streets – a free man in a free country. London was the only capital that had withstood the German onslaught of Europe – the single hope that victory would come. I saw with my own eyes the price that London, and Londoners, had paid in destruction and death. But even the V1 and V2 rockets with their random terror couldn’t break their spirits and now, with the capture of the rocket-launching pads by the Allies, uncertainty and fear had disappeared. People roamed the streets, the double-decker, red busses roared by, and the extensive network of trains rumbled underground. I saw, with great satisfaction, that everything we had heard from the BBC on our illegal radios was true.

Each evening we heard the heavy drone of hundreds of bombers as they flew eastwards. Next morning they returned, after giving the enemy Germans a taste of his own medicine.

Kingston House

Kingston House was a large, attractive office block. How encouraging it was to see all those Norwegian uniforms. I was enrolled in the Royal Norwegian Air Force, Transport Command, AC2-ACH (Aircraft man and Aircraft helper, lowest rank,) No. 5582. Before I could start, however, an officer from the General Staff came to me with a list of people who wanted to interview me. I had, after all, recently been inside the headquarters of the German High Command in ‘Fortress Norway.’ Again, before I could begin, another officer came – he had parachute wings on his uniform – and said that they urgently needed to drop an Intelligence operator in Norway. ‘Was I willing?’ I replied that I could neither operate a radio nor handle a weapon, and that he, as a trained spy, must be more suitable for such a job than an overgrown schoolboy from Lillehammer. I’ll never forget the answer he gave: ‘Yes, technically I am a better spy than you. But, number one, I have lived here in a free society for so long that I would be unmasked by elementary mistakes. Number two, you have proved that you can manage very well in an enemy environment, and finally you have just come from there so you will manage much longer than I could.’ I asked if I could take a trial jump but there wasn’t time for that. (It is twice as dangerous to drop twice as it is to drop once!). Finally I had to say ‘OK’.

However, the captain postponed the drop when he saw the list of people who wanted to interview me, Good intelligence officer that he was, he knew that cancelling the interviews could look suspicious and may have been correctly interpreted by German spies. So off I went, wandering along countless corridors and into numerous offices.

One evening, in the canteen under Hotel Shaftsbury, I met my dear YMCA friend Fredrik Grønninsæter. What a coincidence: we had spoken together in Lillehammer the day he had to leave for Stockholm. There he had volunteered for the RAF, flown to England, been on a crash course to be an aircraft mechanic, served in Belgium and was now on a short leave in London. It’s a small world.

When I finally completed the interviews I reported to the captain. He raised his eyebrows and said: ’No, the need for spies is over, – Hitler shot himself earlier today, – you are a civilian now. Actually I was still in the Air Force and could proudly wear my new uniform with the Norwegian-flag shoulder patch.

Peace – and the celebration in London

VE Day in London was incredible and I was all over the place, beginning with Buckingham Palace where King George proclaimed the total victory over Germany and its European allies. We sang our way through the streets, comrades for the evening of all nationalities. The pubs were sold out of beer early, only a few in the crowds had a bottle or a glass in their hands. All the singing, shouting and cheering played havoc with our vocal cords. That night I slept on the floor in the apartment of a chap from Hamar I had met by chance – our world had changed radically. Our dreams that had lasted five long, dreary years were suddenly a reality -soon we would be home!

Farewell to London

Of course soon could not be soon enough. There were not enough planes or ships to get all the Europeans home immediately. Besides, there was work to be done – the offices had to be cleared, documents packed, and equipment returned. We joked about bringing educated men from Stockholm to London just to be packers. After two weeks of working and occasional sightseeing our humour began to wear thin. We didn’t know what was happening at home. Through a programme on the BBC I was able to send a message that I was in London and all was well. But when the first priority of passengers for Oslo was posted AC2-ACH 6682 Storrusten was not on the list.

However, I had other priorities – and another alternative. I took the night train to Edinburgh, sleeping on the floor under a newspaper. At Leuchars airport there was nothing to do but wait for a last minute cancellation. I waited 4 days before the miracle occurred and I boarded a Loadstar. Over Lindesnes the clouds cleared and a summer-decked Norway unfolded beneath us. As we flew above the coast people in boats waved up at us. Many of the returning service men and women had been away much longer than my paltry two and a half months. I don’t think there was a dry eye amongst us when we landed.

Oslo

The girls at the housing office probably thought that I was an officer because they gave me a single room at the Mission Hotel instead of a bunk at some out of the way barrack that I deserved. The first thing I did was to ring home and was relieved to hear that all was well. Nobody told me about father’s critical operation at Grini. I said that I would come home as soon as possible. That evening the streets of Oslo began to fill with people preparing to welcome the King and family next day. In the middle of these crowds, I met, wonder of wonders, Kiri – the girl who saved me from the Gestapo and gave me the chance to escape. Talk about a re-union! We danced the night away and as there were few in Air Force uniform I found myself a popular figure. I missed my Aase-Berit of course but there hadn’t been time for her to get to Oslo after my arrival. The Royal Family landed next day and drove through the streets in triumph – with Milorg men as honour guards in each car. Nobody seemed to notice the members of the Government. I know what I would have liked to have done to Mr Koht!

The festivities ended for me that evening when, without a leave permit without money, and without a ticket, I stowed away on the train to Lillehammer.

Home Again

“It was unbelievably wonderful to be back with my family. My pitiful soldiers pay in London hadn’t stretched to more than 3 aprons adorned with allied flags that I had bought for the three women in my life: mother, sister, and girl-friend. Father looked like the starved concentration camp victim he was but he was not in too bad a shape. The day he came home from Grini he, normally a tight-lipped man, had talked to Inger and Asse-Berit for more than two hours. For the first month of peace Aase-Berit and Inger took turns at the Gestapo HQ Trarar, guarding the arrested Norwegian Nazis.

Lillehammer had never looked as attractive as in those balmy June days. But I didn’t see many of them – duty called.

Gestapo Headquarters

Erling’s ‘duty’ for the Air Force took him to Fornebu Airport, Oslo, where his English and German came in useful. Traffic between Oslo and other European capitals was brisk, with both civilian and military personnel. Dakotas (later DC3’s), Lockheed Loadstars, Catalinas and Sunderlands were all put to use – the latter to coastal towns with no airports. To modern travellers some of the procedures seem pre-historic, the problem of balance, the Lockheed Loadstar was the worst because it easily became tail-heavy. The solution was simple: passengers were lined up, the heaviest first, the middleweights next and the lightest at the end. They then boarded the plane and sat from fore to aft in the same order.

One day we used balance was used as an instrument of revenge when a group of German officers arrived to board two Dakotas for their journey to British imprisonment. They carried large, heavy bags which, to Erling and his colleague from Bergen, were full of stolen property. I told the pilot to fill the tanks with extra petrol and then, when the officers came to weigh their bags, my colleague carefully put his foot on the scale and added an extra 20 kilos. Each man had to leave one bag behind: This was the only act of revenge against the Wehrmacht that I can remember But my ‘finest hour’ came when I had completed the instructions on use of the life jacket on the plane. I then said: “Und jetzt meine Herren fahren wir gegen Engeland. (A reference to the song German troops sang as they marched through the streets of Norway during the invasion.)

Similar invasions throughout Europe, concentration camps and war devastation had uprooted millions of people. Some came through Fornebu. Daily we saw poorly clad, sallow faced, thin, shadows of men and women limp down from the planes. They had little or no luggage, no money, and nobody to meet them. A reception committee took care of them until they could make contact with family or friends.

Sometimes the duties were of a more personal kind: Some of the smart Norwegian officers who had served abroad had married, now their Norwegian girlfriends were waiting for them, laughing and cheering – ignorant of their ‘boyfriends’ new marital status. “What should we do?” they asked.

Erling writes that he had always been thankful for “…the hard work, and diet of corned beef and tea that he experienced at Fornebu in the tropical summer of 1945.”

When traffic slowed down at Fornebu, Erling was transferred to the travel office in Oslo He tried to get his ‘demob’ from the Air Force to continue his studies but no, he had to remain until the new, private, DNL (The Norwegian Air Transport Company) could take over.

He thought he could continue his studies while working and took several preparatory semesters without attending lectures. But finally he had to choose: study or employment?

On March 1 1946 he was finally discharged from the Air Force and employed by DNL.[7] His career in the airline industry had begun.

Storrusten – Epilogue

It is May 18 – the day after Norway’s Constitution Day

April and May are studded with days that bring back memories – black memories of April 9th 1940 and the years that followed – and bright memories that started 5 years later when the war ended. The May 17 celebrations that year marked not only the signing of the constitution but also the restoration of Democracy after 5 years of resistance to the occupation. Nowhere was the celebration greater than in Lillehammer – the last remaining stronghold of the once seemingly invincible Third Reich.

Else and I are driving north from Oslo towards Lillehammer with Aase-Berit and Erling Storrusten on a short visit to their hometown. As we approach, driving along a road running parallel to the river, Aase-Berit tells us about her experiences on April 8, 1945. This was the day peace was proclaimed in Europe but the German High Command in Lillehammer had not yet accepted the surrender.

“I was a Red Cross worker and that morning, after a telephone call, I went to the town center where we made sandwiches for the Russian prisoners at Jørdstadmoen, the military camp just outside Lillehammer. Considering the rationing and chronic shortages it was incredible that so much food had been donated – liver paste, cans of sardines, bread, and margarine. When the sandwiches were ready we were told that only the Red Cross drivers would be allowed into the camp. We complained that this was unfair discrimination and we finally got permission to accompany the drivers. Four German officers stood at the camp gates but they did nothing to hinder our driving through – a wonderful feeling after years of trying to avoid Germans – we didn’t realize then that the German forces in Norway had not yet capitulated. Our meeting with the prisoners was horrifying – the bunks in the huts rose three tiers from the floor and three prisoners shared each bunk. They were terribly thin – mosts of them suffered from advanced TB, many of their colleagues had been worked to death, many of those we met would succumb to their illnesses and for the rest – after a brief spell of freedom in Lillehammer – transport to Russia and, for most of them, onward to a certain death in Siberia.”

At Jørdstamoen, which is still a military camp, the young soldier in the guard-house had difficulty in explaining where we would find the Russian Cemetery but he gave us general directions. A signpost showed the way from the main road where an unpaved track led us past a nursery school and around a copse of pines to the tidy, tranquil, tree shaded resting place of 954 tortured souls.” It is ironic that Lillehammer, which before the war was famed for its invigorating fresh air and modern sanatoria, should have become the site of so much deadly sickness.

Aase Berit and Erling Storrusten

at Russian Cemetery

Aase-Berit has another story about the 8th of May. “My parents were returning from a ‘celebration’ at my grandparents’ house which was on the road leading up to the Tourist Hotel. It was about 11.30 pm, the night was damp and misty. They had just turned the corner onto the main road through Lillehammer when two limousines, with standards flying, pulled up beside them. A window was rolled down and a voice asked if they could direct them to the Lillehammer Tourist Hotel. This was easily done and the cars pulled away.

Only later did my parents realize that they had made their final contribution to the war effort by directing the Allied Commission to its meeting with General Böhme.” The four members of the commission were: Brigadier R. Hilton, the leader, a traditional, ‘no nonsense’ British officer, Colonel R.A. Hay, who had served in Germany and spoke German fluently, Squadron Leader C. Peto Bennett, half Norwegian on his mother’s side, and the Norwegian Naval Commander Per Askim, who had been in command of the Coastal Defence Ship ‘Norge’ when she was sunk in the harbour at Narvik on April 9 1940. A distinguished group of four men sent to convince the leader of almost four hundred thousand armed troops that there was no alternative to the acceptance of the terms of surrender.

Erling explained how small town Lillehammer came to be the focal point of a world war:

Towards the end of 1944, General Lothar Rendulic had been in charge of the German forces and their withdrawal from Finland and Northern Norway. He was responsible for carrying out Hitler’s ‘burnt earth’ policy during the retreat. On December 18th 1944 he replaced von Falkenhorst as Commander in Chief of all German forces in Norway. He chose Lillehammer as his Headquarters and requisitioned Lillehammer Tourist Hotel as his center of operations. He began a hectic programme of fortifying and securing the wooded area around the hotel. This was the background for Storrusten’s spying activities.

General Franz Friedrich Böhme replaced Rendulic as Commander in Chief of the German Wehrmacht in Norway on January 18th 1945. In 1941, as the C. in C. Serbia, he was responsible for reprisals against civilians including the execution of 7000 men and boys in Kragujevac. Like Rendulic he was Austrian by birth, and like Rendulic he was of the ‘old’ officer type – strict, competant and completely loyal to Hitler as “Der Führer”.

Gateway to hote

Neither Rendulic nor Böhme had any respect for Terboven and Quisling – hence the choice of Lillehammer as headquarters – far away from the political infighting and intrigues of Oslo. Another reason was that Lillehammer was strategically more suitable to resist and repulse any attack from Sweden.

The Lillehammer Tourist Hotel has been greatly expanded since 1945 and is now owned by SAS. At the gateway to the hotel, Erling points to an electrical transformer: “That was a pill-box in ’45 – good to see that the concrete has come to some use.” After checking in we walk behind the hotel, past the empty swimming pool, and begin to look for the entrance to the communications center.

Bunker Entrance

The last time Erling was here he found it but now, probably because of the new construction, the entrance had disappeared. “The communication center was filled with the latest equipment and staffed by experts – truly an important spot during those nervous days in April 1945,” said Erling. We wound our way up the hillside away from the hotel and Erling explained that beneath our feet was a huge bunker designed for supplies, equipment and shelter. Where Erling had made his way through tree studded and rock scattered terrain, were now smart houses, well-tended gardens and black-paved roads. But not far from the new buildings, wilderness re-appeared: a rushing stream and a muddy track leading to a half-hidden, half open iron door at the base of the hill. “One of the entances to the bunker” said Erling. Inside it was dark, nothing much to see; a black hole stretching an unseen distance, stagnant water, debris. Imagine the misery and the pain of the hapless prisoners who had been forced to excavate this useless, oversized rabbit-warren.

Villa Wang

Before entering the hotel grounds again we took a narrow side road that led to a low, grass-roofed, log house. Villa Wang, as it was called originally, had been requisitioned to accommodate Rendulic and Böhme. On the wall beside the door is a brass plate with the insription: In this house the Allied Commission delivered the terms of capitulation to the German High Command in Norway. May 8 1945.

Immediately after the war a similar plate hung erroneously on a wall of the hotel’s library. Now there is nothing to indicate that for a few days in May 1945 Lillehammer was the scene of one of the great uncertainties of WW II. Throughout our trip Storrusten talked about the events, the questions, the fears and the consequences of those days. Böhme was the undisputed leader of almost 400.000 armed men. His fanaticsm and ruthlessness had been demonstrated in Serbia – and could easily be reignited if challenged in Norway. He had advised his commanders of the capitulation information he had received from Hitler’s heir, Admiral Dönitz, but he had not responded to the order to contact the Allied powers at SHAEF.

At 2345 when he finally faced the Allied Commission in Villa Wang, his first words were: “I stand before you as Commander in Chief of the 20th Army and as Minister of Defence for Norway. I assure you that I will comply with your terms loyally…” but then he added: “the German Forces in Norway are undefeated.” He seemed to be saying that he had control of his troops, he was willing to co-operate, but was unsure that the Allies could control the quasi- military forces in Norway. Böhme found the 21 Articles in the Capitulation hard to take, he tried to negotiate but Hilton was unmoved – the terms were non-negotiable. At 0100 the meeting ended, the commission chose not to stay at the German Headquarters and were driven to the Lillehammer Mountain Hotel at Nordseter.

We, however, spent the night at the hotel and next morning we drove around Lillehammer with Erling and Aase-Berit as enthusiastic guides. Lillehammer seems not to have been so drastically ‘modernised’ as, for example Oslo. There are still long streets of wooden houses even close to the center. The homes of Aase-Berit and Erling remain unchanged, as are the buildings where Aase-Berit made sandwiches and where Erling sketched his map. The large villa that had housed the infamous Gestapo now squatted derelict and dusty – overshadowed by a busy highway. We visited the British Cemetery, the last resting place for some of the ill-fated, ill-trained and ill-equipped British Force that tried to help the Norwegians stem the German advance up Gudbrandsdalen. Perhaps even ill-trained is an exaggeration – at least for Private W. Brown of the Leicestershire Regiment: he was 17 years old when he was killed on April 28 1940. At the main cemetery we paid our respects to some of Erling’s war-time colleagues, including the doctor who had given him the fake disability certificate.

After an inspiring morning we drove out of Lillehammer, past the home of Sigrid Undset, and along the road taken by the Allied Commission in May 1945. On that lonely road it was easy to appreciate that the four men were apprehensive and wondered if they had, after all, been tricked by Böhme. Except for an occasional cabin – which wouldn’t have been there in 1945 – the area is uninhabited. The road cuts through a wilderness of forests that eventually turn to scrub and finally to barren highlands. Then, suddenly, signs of life – signs of all kinds now, advertising signs: cabins, hotels and apartments for rent and for sale, but in 1945, only a gaunt hotel and the vast sprawl of the German barracks. The Norwegian staff at the hotel welcomed the Allied Commission with a slap-up feast that continued into the early hours. The commission returned to Oslo next morning where they learned that Terboven had committed suicide just minutes before their meeting with Böhme the previous night.

We visited some of the newer tourist facilities in this popular winter holiday resort and drove down the road that roughly followed the route that Erling had taken on his flight from the Gestapo. The drive was pleasant and peaceful in the sunshine but it was not difficult to imagine a solitary man struggling up the steep incline, finding his way in the dark, the ground frozen, the trees hanging heavy with snow and the prospect of a hazardous lengthy journey before him. Erling passes it all off lightly, “It wasn’t so bad – I was used to long ski-trips” he said. In 1985 however, in a newspaper interview, he remembered differently: “…it was a terrible trip. From Sjusjøen we went on skiis, the snow was wet and stuck in lumps to the undersides making the going difficult. I was worried about my father who was ill and had been arrested by the Germans. I mentioned this to my guide who told me to relax – he had been told to let me know that father had been released.” The guide, Albert Taraldstad, met Erling again for the first time at the memorial ceremonies in Lillehammer on May 7 1985. He told Erling that the news about the release of his father had been made up on the spur of the moment – and that he had been carrying a pistol with orders to shoot Erling if there was any danger of being captured by the Germans.

On our way back to Oslo we stopped at Elverum Folkehøyskole. The King, Parliament and Government met here on April 10th 1940, the King gave his resounding “No” to German surrender demands, and Carl Joachim Hambro penned the famous ‘Elverum Mandate’ Our next stop was at Midtskogen, site of the battle where, on the night of April 9/10 a small group of Norwegian patriots halted an elite German force and allowed the Royal Family, Parliament and Government to continue their flight and eventually escape to England. There are informative displays at both these historic sites.

We ate lunch at a roadside café with a splendid view over lake Mjøsa. Afterwards we left the motorway and drove along the old road that hugged the lakeside and and seemed to live a quiet, forgotten life of its own. We were looking for the memorial stone for another of the early confrontations in 1940. Finally, cursing the lack of signs, we found it; a simple stone column rising from a grass mound and facing the lake. In April 1940 the lake was frozen,allowing the Germans to bring reinforcements to the hard-pressed group trying to break through the makeshift Norwegian line at Strandlykkja. The Germans may have mistakenly believed that the Royal Family, Parliament and Government had taken this route but all they found was an early indication that their occupation of Norway was not going to be an easy task. (Min Far Henry)

Throughout the trip Erling had kept up a running commentary: why this village was important, when that church was built, where this road led to and even what kind of rock formation we were driving over. It was like being on a moving geography/history/social studies lecture. Of course we could expect no less, in 1976 he wrote ‘The Most Beaurtiful Sea Voyage’, a book describing the coastal voyage from Bergen to Kirkenes. If you write ‘Erling Storrusten’ in Google you get several hundred ‘hits’ – most of them about this book. A Director of the Norwegian Automobile Association for 10 years he had also been responsible for the publication of the bi-annual ‘Road Book’ – a 4-500 page compendium of travel information distributed to the 400,000 members of the association. To compile and update this guide, Erling and Aase Berit criss-crossed the country; observing, interviewing, testing, cataloguing and writing – a mammoth task in the days before PC’s, and one which he continued to fullfill for a couple of years after retirement.

Retirement is not what it used to be and Erling is as busy as ever with weekly Rotary meetings, writing, and lectures. However, the ‘Pilgrims Journey ’ project is what he talks about most and what I suspect gives him most satisfaction. The project began in 1997 and since than more than 10,000 children have participated. Erling and 15 colleagues spend 16 days each spring and autumn meeting and guiding all the sixth grade children from local schools. The tour follows in the footsteps of the ancient pilgrims on the first leg of their 650 km. trip from Haslum Church (near Oslo) to Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim. “The children walk only a symbolic 9 kms, but it’s a historic journey during which they learn about faith, trust and traditions” says Erling – who is probably thinking about how he learned these attributes during his childhood.

Geoff and Else Ward

Asker, 2007