Courier of our Lord

On November 30 1939, armed forces of the Soviet Union attacked Finland. To the rest of the world this aggression was an expansion of the festering situation in central Europe, where Hitler, just two months earlier, had forced Poland into submission. Norway did not relish the thought of having an enemy USSR on her northern border but was able to give only minimal military and humanitarian help.

The Norwegian Red Cross had sent a volunteer ambulance team to Finland in December 1939. A second team of 8 doctors, 14 nurses, and 3 drivers/assistants, left Oslo on February 7. Destination: Sotkamo in Central Finland. One of the drivers was an angry, 20 year old theological student Hans Christen Mamen: He was angry because he realised the possible consequences of the German and Soviet aggressions.

The Norwegian Red Cross had sent a volunteer ambulance team to Finland in December 1939. A second team of 8 doctors, 14 nurses, and 3 drivers/assistants, left Oslo on February 7. Destination: Sotkamo in Central Finland. One of the drivers was an angry, 20 year old theological student Hans Christen Mamen: He was angry because he realised the possible consequences of the German and Soviet aggressions.

It is September 21 2006 and Hans Christen Mamen is standing in front of a small audience in Asker public library. He’s a big man, unbowed in spite of his 87 years, casually dressed, almost untidy, but commanding and imposing. He asks if it is OK for him to sit and as he does so he pulls a scrap of paper out of his pocket. The paper almost disappears in his large hand but he explains with a smile: “this is my manuscript – don’t know why I need it – I’ve told this story so many times – but memory isn’t what it used to be.” He is to tell us about his experiences in the years between 1939 and 1945.

He presses a button and a photo appears on the screen behind him: A streaked and shabby ‘Norges Røde Kors Ambulanse’, a shattered building in the background, two men smoking and, sitting on the bonnet, the young Mamen – dressed in black to match his shock of black hair. The mop of hair is only slightly less today – but now it is white.

Mamen decided that he wanted to be a priest when he was 13 years old. As a theological student he followed the military events in Europe with deep foreboding: Germany, Spain, Poland and finally Finland. The drums of war were beating loudly on Norway’s frontier in the North and Mamen felt that he had to do something. He applied to be one of the team that the Red Cross was fitting out to help the Finns and, to his surprise, he was accepted. He had no military experience but he had the qualifications of a healthy young man: he was big, he was strong, he could drive a motor vehicle and he was an active scout leader. What’s more, though he didn’t write this in his application, at least two of his ancesters had been soldiers and adventurers.

Adventure was not a word he would use to describe his experience in Finland. The transition from a peaceful home life on a farm to the dark, bitterly cold, deafening clamour of a war zone was brutal. It took several years for him to erase many horrifying images from his mind. His first job was to write down the information dictated by the doctors during operations. It helped that he had studied Latin at school. From note-taking he “progressed” to assisting in the actual operations. “Assisting” usually meant holding patients still during minor surgery and, worst of all, during amputations. He learned how to clean wounds and how to give injections. He saw many die from their wounds but a patient who died from lockjaw made a particularly indelible impression. From then on he made sure that every injured soldier got a tetanus shot immediately he came in.

The winter war in Finland was brief – a prelude to the longer struggle from 1941 to 1945. The bloody brutality and horrors in Finland were submerged in the cataclasmic events of the wider, world war. Recent photographs released – after 60 years supression – by the Finnish Ministry of Defence, illustrate the atrocities carried out by both sides. Hostilities ceased on March 13 1940 but there was no rejoicing among Mamen’s patients: Finland had lost too much – territory as well as twenty thousand dead, uncounted thousands injured and four hundred thousand homeless.

Mamen returned to Norway on Good Friday, March 22 1940 and immediately returned to his theological studies. On April 6 he became engaged to his fiancé of six years, Ruth. Three days later the country was invaded by Germany. One of the evils that had made Hans Christen angry enough to risk his life in Finland was now threatening his own culture. He quickly became involved with the resistance movement and then, somewhat against accepted security considerations, became a guide for groups fleeing from Nazi persecution across the border to Sweden. Mamen concentrated on escorting Jewish families who, if they had stayed in Norway would have been arrested and deported to a certain death in Germany.

Just getting out of Oslo was a problem. The Norwegian police and the Gestapo were constantly checking identity papers. Worst of all, the passports of all Jews were stamped with a J on one side of the owner’s photograph. One day Mamen was escorting three Jews out of Oslo. They were on a tram, two men and a woman sitting separately, with Mamen at the rear. A Norwegian policeman came on board and asked to see identity papers. The woman was so nervous that she fumbled in her bag and couldn’t, or wouldn’t, find her passport. The policeman moved on saying “I’ll be back”. The two men managed to coverf up the J with their large thumbs, the policemen continued through the car and then came back to the woman. She had found her passport and tried, unsuccessfully, to cover the incriminating ‘J’. The policemand glanced down, said “OK M’am” – although he had obviously seen the ‘J’. “Why did he do it?” asks Mamen in a voice that allows for no doubt the he knows why.

The borderlands between Norway and Sweden were sparsely inhabited, forested areas with few roads: difficult to negotiate for those trying to escape, but equally difficult for the Germans to control. People living in these areas had to carry special ‘Resident’ cards. Those wishing to visit or travel in the ‘border zones’ had to apply for a visitors card. German troops and Norwegian police patrolled the areas and arrested anyone caught without an applicable identity card. Scattered throughout the area were loyal Norwegians who knew every twist and turn of the myriad paths, gullies and streams that criss-crossed their neighbourhood. They lived in isolated farms and cabins. They led a hard life and were used to unexpected dangers. Finding these outposts, silently, and in the dark, was the task of the ‘grenselos’ – literally ‘border pilot’ – a typical Norwegian shipping allusion.

“Yes,” says Malmen, “silence was all-important because we never knew when and where a patrol would appear.” Then he told us about the time he was leading a group of 10, men, women and children. They had almost reached the Swedish border and were being rowed across a lake by a Swedish guide. One of the children started to cry. A man’s voice hissed, “that child is putting all our lives at risk – we must silence it – kill it!” Their Swedish guide stopped rowing and said, “if you stoop that low I will take you back and you can find your own way across the border.”

Another child carved a special notch in Mamen’s memory. Ivar Bermann was only three years old. His father had already escaped to Sweden and he and his mother were on the way with Mamen. It was obvious that Ivar couldn’t possibly manage to keep up with the adults so Mamen sat him in his backpack. This was fine for a while but in the deep, dark, woods the boy became afraid and began to cry for his mother. Mamen realized the danger but what could he do? Like an answer from heaven came a flash of inspiration: “You mustn’t awaken the birds,” he said to the boy, who immediatley fell silent and remained so until they reached safety.

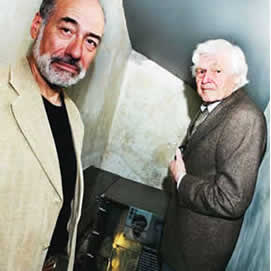

August 23 2006 – a new institution, The Holocaust Center is being officially opened at Bygdøy in Oslo. An elderly man with a shock of white hair greets a younger, dark haired man. They enter one of the rooms and there, in a corner, is their story: a backpack and a placard –young Ivar Bermann, Hans Chr. Mamen and the sleeping birds meet again..

Photo: Øystein Franck-Nielsen

Mamen hasn’t looked at his ‘manuscript’ once and now he has finished. “Are there any questions?” he asks.

I stand and ask: “ Are there any publications that tell about your work during the war?”

He replies that a reporter from the newspaper ‘Asker and Bærum Budstikke’ had written a book.

A few weeks later I bought and enjoyed reading “Vårherres kurer”, ( “Courier of our Lord”), written by the respected editor and journalist, Ivar B.M. Alver.

Later, on a snowy day in January, we invited Hans Chr. Mamen to lunch. He lives only a few minutes drive away from us, in a house that stands on what used to be part of the farm where he grew up. We asked him for a few more details about his work as a “border pilot” and he told us that the journeys often began with the refugees coming to a rustic cabin in the woods not far from the farm. “It is still there” he said, “but in a sorry state of repair and nobody feels responsible for maintaining it.”

The cabin was called “Mor-ro” – “Mother’s peace” and, in Norwegian, a wordplay on “ro” – “fun.” The first 4 occupants, however, were not seeking to escape from Norway but had come to Norway from England. They were the first members of Milorg to land by parachute in the hills behind Oslo. After a few days at “Mor-ro” the group, minus one who had been sent back to England, moved into the hills again and operated as weapon instructors for members of the growing resistance movement.

Mamen said that he had had some problems with the idea of armed resistance for himself but still felt a call to work against the occupying forces. “My ‘resistance’ was to help as many persecuted Jews as possible” he told us and continued: “ I usually took only three people with me at any one time because any more became unwieldly and increased the chances of being captured.” Most of the groups comprised women and children because many Jewish males had either been arrested already or had escaped before the infamous round-up on October 26th 1942.

Mamen himself had to flee to Sweden in December 1942 and he told us what happened:

“A couple of Norwegian policemen came to the farm in Asker and asked for me. My mother told them that I was studying in Oslo, so they left. She immediately called the college and asked the secretary to give a message to Hans Chr. Mamen. ‘Of course’ the secretary replied and a few minutes later I was told, ‘pack your suitcase.’ In the meantime mother had gone down to the telephone exchange and asked if they could change the date on the telephone call she had just made. The call was erased completely. I left in the middle of a lecture and went first to an aunt. She was having a birthday party so I left and headed for one of the college staff that I knew I could trust. He and his wife put me up and passed on a message to Ruth, that I was in hiding and preparing to leave for Sweden. Ruth insisted on coming with me and after a heated discussion with her parents, who were not too keen to have their daughter leave them, we started to make arrangements. The trip turned out to be more exciting that we had expected.”

“First we took a train to Mysen and then, covered by a tarpaulin in the back of a truck, we were driven to a normally ‘safe house’ just two hours march from the border. The owner told us that there had been a razzia in the neighbourhood so it wasn’t wise to stay there. It wasn’t wise to continue on foot either for the new snow would show clear tracks for any border guards who might be around. The man who drove us from Mysen had a permit to to fetch wood from this area so we agreed that it would be better for him to ‘legally’ drive us closer to the border. The only snag was that a Norwegian Nazi sympathiser, who lived in a house right beside the border was known to stop and search all vehicles. However, our driver assured us that the man was afraid of the dark – and anyhow, if he did come out, he (our driver), was armed would shoot his way through. Back under the tarpaulin we held each other close and finally the truck drove without hindrance past the house and into Sweden. We got down from the truck, I stuck a Norwegian flag into the backpack and we went down on our knees to thank God for bringing us to safety. Then we continued through the woods until we saw what, for me, was the familiar light from the lamp in Gustafsson’s hut. Gustafsson was a woodsman who would guide us on the last stage of our journey to Töckfors.”

During the night, another 20 refugees reached the hut. Several of these were well known in Norwegian cultural circles. Next day, at Töckfors they encountered Åke Hiertner, a representative of the Swedish authorities who had proven to be a strong Nazi supporter. Mamen told us that in a museum after the war, he had seen a document that listed all the refugees that had arrived at Töckfors. Hiertner had sent eighty of these back to Norway – and to an unknown fate. He was unfriendly but gave Mamen, Ruth and the others in their group no problems and the next day they were sent by truck and train to Stockholm. Mamen remembers that at while they waited for the Stockholm train at Arvika station they were served hot chocolate by pupils and staff of a nearby school. “This was the real face of Sweden in those years, not the anti-Norwegian official at Töckfors” said Mamen who also had time to visit a relative who lived in Arvika.

In Stockholm Hans Christen and Ruth took out marriage banns and on January 24 1943 they were married among his Swedish ‘family’ in Arvika. After a short time in Stockholm Mamen decided to continue his theological studies at the University in Lund where there were fewer Norwegian students than at the more popular Uppsala Univeristy. Ruth got an interesting position in the University Library so the newly married couple had little time to think about the dangerous work they had left behind.

Not that Hans Christen had forgotten Norway and the debt he, and many others, owed to the Swedish people. Whenever the opportunity arose, he wrote, preached and lectured about the situation in Norway, the impørtance of Swedish assistance and the certainty of an Allied victory. He also met several of the families he had helped to escape, most of whom remained life-long friends. In 1980 one of these families, who had become Swedish citizens after the war, recommended Mamen for the “The Righteous Among the Nations” medal – with the right to plant a tree in the Holocaust memorial at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Later, in Oslo, Mamen was appointed honorary citizen of Israel.

Not that Hans Christen had forgotten Norway and the debt he, and many others, owed to the Swedish people. Whenever the opportunity arose, he wrote, preached and lectured about the situation in Norway, the impørtance of Swedish assistance and the certainty of an Allied victory. He also met several of the families he had helped to escape, most of whom remained life-long friends. In 1980 one of these families, who had become Swedish citizens after the war, recommended Mamen for the “The Righteous Among the Nations” medal – with the right to plant a tree in the Holocaust memorial at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Later, in Oslo, Mamen was appointed honorary citizen of Israel.

Proudly he showed us the framed certificate of his citizenship and said that he was the only person in Scandinavia to be so honored.

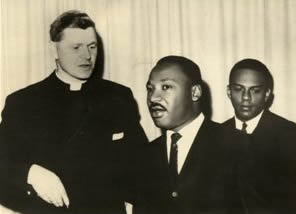

At the same time he told us that his interest and concern for minorities continued after the war and were stengthend during a year he spent as an exchange- priest in the USA. He took out another photograph – a young Mamen with two black Americans. He was not surprised when we recognised Martin Luther King but I don’t think he expected us to know that the other man was Andrew Young – UN Ambassador and the first black Mayor of Atlanta, Georgia. Mamen had writtten a long article about King and was invited to meet him in Oslo after he had received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

At the same time he told us that his interest and concern for minorities continued after the war and were stengthend during a year he spent as an exchange- priest in the USA. He took out another photograph – a young Mamen with two black Americans. He was not surprised when we recognised Martin Luther King but I don’t think he expected us to know that the other man was Andrew Young – UN Ambassador and the first black Mayor of Atlanta, Georgia. Mamen had writtten a long article about King and was invited to meet him in Oslo after he had received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

Early in 1944 he finished his studies in Lund and was immediately seconded to the Norwegian Reserve Police, a unit organised to enter Norway and assist in the transition when the war ended.Mamen remembers that the first camp was muddy and miserable – a typical “boot camp”, with hard physical training, uncertain hours and rigid discipline. A tough life for youngsters who were more used to listening to lectures than making long marches at night.

But after only three months in the reserve police he was told to report back to the Norwegian Legation in Stockholm – section MI IV. This was in August 1944. The end of the war was in sight but there was no telling what the Germans in Norway would do. Would they continue fighting? Would they revert to the ‘burnt earth’ policy used in Northern Norway? Or would they relinquish power peacefully? MI IV was Milorg’s office in Sweden and Mamen was excited to be once again working for the Norwegian Resistance. Knowing the border lands as he did, Mamen was given the task of helping to plan routes to and from Norway that could be used by military transport and units in the event that fighting continued in Norway when the Germans in mainland Europe had capitulated. He also reverted to his role as guide, this time in the reverse direction, piloting Milorg agents and other Norwegian resistance workers from Sweden to Norway. From time to time he also carried important mail, including maps and photographs, and sometimes even equipment, from Stockholm to the advance camps near the border.

The equipment, men and arms were never used, but their existance, and the threat of well-organised military and civilian forces, resulted in a peaceful ending to the German occupation of Norway. Hans Chr. Mamen, with his wife and young son were in Stockholm when peace came. He remained for a while and helped tie up loose ends at the ministers’ office in the refugee center and then returned to Norway to take up the threads of his life. His Swedish exam results were accepted by the Norwegian authorities and he became a revered minister, writer, lecturer, editor and community leader.

Else and Geoff Ward

Asker, July, 2007