Throughout the war years the Resistance Organizations in Norway and, indeed, in the whole of occupied Europe, were dependent upon outside sources for supplies, equipment, ammunition and specialist personnel.

Much has been written about the men and women on the ground, who watched, waited and finally collected, hid and distributed these supplies, but what of the organisation behind the drops and the men who flew the planes – often in poor weather and always in danger of being shot down by enemy flak or fighters?

In July 1940, the British Special Intelligence Service, (SIS) established a separate unit, Special Operations Executive, (SOE) to organize, assess, and co-ordinate the requests for supplies. At SOE headquarters in Baker Street, London, each occupied country had its own section. SOE was the brainchild of Hugh Dalton but Winston Churchill is credited with exhorting the new unit to “Set Europe Ablaze.” Later, SOE operations extended to all corners of the world-conflict.

SIS and SOE used the new (March 1942) Tempsford Airfield near Cambridge as a base for many of their most secret operations. With their Hudson, Halifax, Lysander, Stirling and Whitley aircraft the RAF Squadrons 138 & 161, have been referred to as the Moonlight Squadrons, The Cloak and Dagger Squadrons and, perhaps even more tongue-in-cheek, The Tempsford Taxis! The official name was the more prosaic ‘Special Duties’. Whatever the name, General Eisenhower said that the disruption to German troops caused by SOE-supported Resistance Movements throughout occupied Europe played a very considerable part in the complete and final victory.

Night after night, during the period one week before and one week after the full moon, the intrepid pilots and crews delivered arms, ammunition, radios and other equipment to pin-pointed areas from the Arctic Circle in Northern Norway to the shores of the Mediterranean. They also delivered and picked up agents, known to the crews as “Joes”,(though “Joan” would have been more applicable for some agents), either by parachute or by landing at night in isolated fields, usually relying on simple torches as their landing lights and guidance system.

On a lighter note, but with a serious intent, the flights sometimes carried pigeons. ”The pigeons…had their own little parachute, they were in a little cage made of cardboard and they had food and some water in there, and we used to try and find a nice quiet spot for these so that they would be all right. We would drop them and watch them go down and sometimes quite useful information came back, I gather. We didn’t see that of course. But there’d be a little pencil in this cage and a piece of rice paper and they were supposed to get hold of these pigeons, you see, write a message and put it round their leg and send them back”.1

Tempsford based aircraft, flying out of their forward base at RAF Tangmere on the south coast, dropped supplies to the Czech resistance that led to the ambush and assassination of the “Beast of Prague”, S.S. Intelligence Chief Reinhard Heydrich on 27 May 1942. Vincent Auriol, General de Latre de Tassigny and Maquis fighter, Francois Mitterand, were among the important men evacuated from France. Knut Haugland, William Houlder, Gunnar Sønsteby and Reidar Kvaal were just a few of those parachuted into Norway and Andree Borrel, Violette Szabo, Yoland Beekman and Lise de Baussac were four of several female agents, mostly originally French citizens, who were involved with SOE operations. Of the females, only Lise De Baussac survived, the others were captured and murdered.2

The life of ‘special duties’ pilot was often that of a lone wolf; he had no fighter escort and exploited low flying under the most difficult conditions, contending with “flak” and fighter defences. The work was highly exacting, requiring much preparation and accurate navigation (that is, purely by calculation). Once over the drop-zone, the aircrew had to unload their cargo quickly enough to prevent the packages being scattered – and to avoid being spotted by local enemy forces. When delivering or picking up agents, the aircraft were on the ground for only a few minutes.

The Germans were acutely aware that these flights fuelled the resolve of the Resistance forces and they did all in their power to discover their origin. Hitler himself ordered his minions to “…find this viper’s nest and obliterate it.” At least 2 German agents were apprehended in the vicinity of Tempsford but the “Abwehr”, (German Military Intelligence) never pin-pointed its exact location.

The pilots and crews at Tempsford came from the whole of occupied Europe as well as from the British Isles and Commonwealth countries. A devoted band of enthusiasts keep alive the memory of the men and women who served there. Steve and Pam Harris were our first contacts and Steve wrote: “A whole Norwegian SOE section took over one of the large country houses close to Tempsford Airfield (Hassells Hall-ancestral home of the Pym family), for last minute training of agents, before they were dropped into Norway. One of the experienced Tempsford pilots who was, naturally, keen to take on the Norwegian missions was himself a Norwegian, Lt. Hysing-Dahl. He flew a full tour of 30 missions, and then returned later for another tour of duty. Tempsford enthusiast and author Robert B. Body (see links below), provided us with some of the de-briefing reports made by Hysing-Dahl. Another connection with Tempsford came about through a birthday greeting to Egil Sandberg in “Aftenposten”. When we spoke with him shortly afterwards he told us that he had been stationed at Tempsford. This was the first time we had heard of one of the war’s best kept secrets.

After the war, the airfield has reverted back to its farm-land origins – only the supply barn remains – but in St Peter’s Church Tempsford there is a plaque commemorating the men and women who flew and serviced the “Tempsford Taxis”

Links:

I met Egil Sandberg shortly after his 85th birthday, on a cold, snowy January day in 2008. He was not in the best of health but his eyes were bright and his voice easily betrayed his Bergen origin. I met him again in November. He had just recovered from a bout of pneumonia and could only speak in short periods. I asked him if he knew Per Hysing-Dahl and he replied “He was one of my best friends.”

Egil was 18 when the Germans occupied his hometown. on April 9, 1940. The day before, in a football match for Djerv against local rival Minde, he had scored a goal.

He remembers the Germans marching through the street – “something we’d never seen before,” and he has to catch his breath when he continues: “I was an apprentice in a building supply store – we imported goods from Germany – my boss, the owner, was killed in the fighting on April 9th”. In addition to working, he studied at business school in the evenings.

The death of his boss obviously made a deep impression on young Egil and he soon decided that he would ‘‘run away to fight the Germans abroad.” He told his brother, who was headmaster at a school in Bergen and who helped Egil to improve on his scanty school English. He did not tell his parents about his plans to leave the country.

A naval officer helped Egil to plan his escape to England: first to Kleppestø then to Juvik and finally “on a boat with a fantastic skipper who knew exactly how to navigate in those uncertain seas. We sailed straight to the Shetland Islands.”

How did he feel about leaving Norway? “It was satisfying to get away – I simply had to do something against those who had occupied my country.”

Training field – Little Norway

The first stop in London was a 6-9 week course at the Recruit School and then “a very rough trip” across the Atlantic to Halifax in Canada. At Little Norway, near Toronto, he was told that he could wait several months for pilot training or start training immediately as a radio operator.

He chose the latter and a couple of months later, he was heading back across the Atlantic. Many of the ships in his convoy were sunk by German planes and submarines.

As an RAF radio operator, he was attached to Special Duties squadrons 138 and 161 at Tempsford Airfield. Arvid Piltingsrud, Gunnar Halle, Trygve Kleve and Egil comprised the crew. Arvid Piltingsrud, who had flown and for Widerøe in Norway before the war, had been one of the first instructors at Little Norway. The administration at Little Norway wanted Arvid, his brother Gunnar, Alf Hiorth and Egil to return to Canada as instructors but they preferred to stay in England “where the action was.”

Egil explained that at Tempsford they flew modified Halifax aircraft but instead of the gun turret on top we had an opening in the floor where we could push out agents if they lost their nerve at the last moment. These flights were vitally important – Hitler himself described them as “The greatest menace.” They were also dangerous – 126 planes from Tempsford were lost – but the Norwegian crew survived without a single loss of life.

“It was Little Norway that made the difference” said Egil, “The training there was superb. At Tempsford he flew 37 missions, mostly over continental Europe but at least 4 over Norway. On one return trip, a Polish tail gunner changed places with him for a while (the rear-gunner position was extremely cold and uncomfortable); when they should switch back, Egil found the man slumped in his seat – killed by a piece of flak that had come through the floor.

Egil flew a total of 101 “missions” including a tour on the “Swedish Route” – ferrying agents and recruits back and forth between Bromma airport near Stockholm and Leuchars airport near St. Andrews in Scotland. It was in Stockholm he learned that the naval officer, who had helped him escape from Bergen in 1941, had been killed when the plane taking him to England, had been shot down by a German fighter.

Escape from Norway

Per Hysing-Dahl, Louis Pettersen, and Edvard Rieber-Mohn left their hometown Bergen at the end of July 1941. The head of the Resistance movement in Bergen at that time was Edvard’s father, Fredrik Rieber-Mohn and it was with the assistance of his group that the three friends were able to make their way out of the city. Off the coast further north, the inhabitants of the island fishing communities of Værlandet and Bulandet, gave them food and shelter until a boat could be provided for their trip across the North Sea. After a three-week wait, during which time many other “Shetland travellers” had joined the group, the tiny (28-29 foot) M/B Soløy left Værlandet on August 2 with 28 people onboard, including 6 women. After 36 hours at sea they arrived at Baltasund on August 3rd – King Haakon’s birthday. Louis remained in England for training as a ‘special agent’ but the other two chose to continue on to Canada. After the initial basic training at the Norwegian Air Force training camp “Little Norway.”

Hysing-Dahl lost contact with Edvard when he was sent to Medicine Hat for advanced pilot training. After further training with Bomber Command in England Lt. Per Hysing-Dahl was ready for active duty.

Coastal Command

Lt. Per Hysing-Dahl in London

His first posting was to Coastal Command’s station at St. Eval in Cornwall where he flew Whitley aircraft on anti-submarine patrols over the Bay of Biscay. The “Battle of the Atlantic” was in its closing phase, the Whitley was not the ideal submarine-chaser, and he sighted only one submarine during his entire tour of duty.

Tempsford

In July 1943 Hysing-Dahl arrived at Tempsford to join ‘B’ flight 161 Squadron under Squadron Leader Len Ratcliff. Ratcliff had been one of Per’s instructors at Bomber Command’s Training station. About two thousand RAF personnel served at Tempsford but it was hardly a typical RAF base. The only buildings higher than one storey on the heavily guarded, top-secret, installation were the tower and the hangar. The farm, upon whose land the airport had been built, remained in operation throughout the war, with pigs, hens, corn, and potatoes as convincing camouflage. The airfield buildings, including an original barn belonging to the farm, were placed haphazardly as part of the deception. Not even the local inhabitants of the nearby village knew the nature of the base.

Another aspect of Tempsford was the almost unmilitary informality and a high-degree of ‘team-spirit.’ The leaders never asked their men to do missions that they themselves would not do. The selection of crews itself was most unusual: All the available personnel – pilots, mechanics, navigators, gunners, radio operators and dispatchers, congregated in a large hall with the single object of forming flight crews. As future leaders of the crews, the pilots had to take the initiative – it was like a lottery. The first crew-member Per picked was British navigator Dick Sutton. Then, quite unexpectedly, his old friend Edvard Rieber-Mohn appeared and he naturally joined Per as radio operator. Andy, a mechanic, Lucky, a rear-gunner, Ivor,and another Norwegian, Johan Erland, called ‘Johnny’ completed the crew. Months later that Per realized that with this team he had truly won the “lottery”. In his own words: “…I couldn’t possibly have known that fate had dealt me a crew that I never once wished to change.”

During August and September of Per’s first year at Tempsford, the squadron delivered 10,000 Stenguns, 2,500 pistols, 20,000 grenades, 18 tons of explosives as well as ammunition, medicine, clothes and other equipment to the Maquis in Haute Savoie. The mountain terrain in this part of France was ideal for the resistance forces. In the flat, heavily populated areas of Northern France, conditions were much more difficult and worst of all were Holland and Belgium. The area alongside the river Loire was another area in France where the Maquis was particularly active.

Flights to Norway

In October 1943 Per and his crew made their first flight to Norway – their mission: to drop four men in the mountains close to Røros. The weather lived up to the forecast – shortly after leaving the English coast they ran into “…almost a tropical rainstorm”. Over Norway, the rain turned to snow with the attendant danger of icing. Low cloud made visibility almost impossible – it was a “blind-drop” operation – with no resistance folk on the ground to guide them. After criss-crossing the landing area for 30 minutes without finding an opening in the cloud cover, they had to return. They landed, with practically empty petrol tanks, 10 hours and 5 minutes after take-off.

Thirty-six hours later, they were in the air again with the same four men. This time the weather was favourable. Over the target area, they circled and then, one by one the men jumped into the darkness: Reidar Kvaal, Inge Foseide, Sigurd Haugen and Rolf Arnesen. Eight canisters and two packages containing their supplies and equipment followed. They were to be in the mountains for a long time. Operation Lapwing had begun.

Later the same month they were aloft again with twelve canisters, two packages and two men, Knut Haugland and Gunnar Sønsteby, two of the most experienced Norwegian agents. Once more the operation had to be aborted because of bad weather. Bad weather was, in fact, a more formidable opponent than the Germans. After two further failed attempts, Haugland and Sønsteby were finally dropped on November 18.

During one of the return flights, Knut Haugland told Per Hysing-Dahl that it was his ninth aborted mission. One of these, in August 1942, was the first of the ‘Grouse’ missions – and the start of the Heavy Water Operation.

Unusual “Triple”

In the early months of 1944 the tempo at Tempsford increased as the Resistance forces in France built up their supplies in anticipation of the Allied invasion. The German counter measures increased accordingly. These were tough times for the Maquis and the undercover SOE agents. On the morning of April 10 Squadron Leader Ratcliff faced a difficult task. Normally the missions to France were carried out by individual aircraft, on rare occasions a job required two. On this mission, however, 8 agents waited to be snatched from the grasp of the Gestapo – and that demanded three aircraft.

The essence of the “Taxi” flights was speed. Once the pilot had sighted the landing lights he put the aircraft down, or dropped the parachutes, and got away again as quickly as possible. The actual time spent at the target area can be seen on some of the following de-briefing reports. Two aircraft would spend more time, and three even more. The danger of being discovered by the enemy increased with each flight.

Squadron Leader Ratcliff asked Captain Per Hysing-Dahl if he was game to be part of a “triple” operation – something Hysing-Dahl had never heard of before. He’d been on “doubles”, but a “triple” was new, so he said “yes” immediately. The third pilot, Bob Large, was a newcomer to Tempsford, but he was a seasoned Spitfire pilot. The operation’s code name was “Mineur”

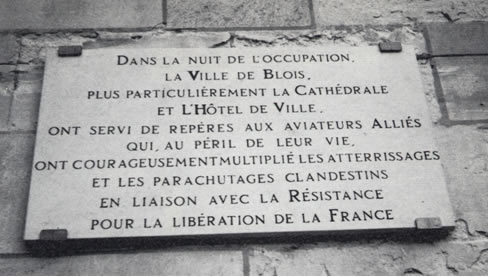

After lunch three Lysanders took off from Tempsford and landed at Tangmere, their forward base on the south coast. Ratcliff in the first aircraft took off again at 2100 and with three-minute intervals the two others followed: Across the channel, over the coast at Cabourg, then south to Blois, with its cathedral tower and Town Hall landmarks, and westward to the final rendezvous over Bléré.

Len landed first, took off again, and Bob followed. As Bob taxied towards the waiting reception group, his engine cut out, a common failure with the Lysander under certain circumstances. With a few adjustments he got it started again and his three passengers clambered aboard. “Your turn, Hysing” said Ratcliff over the intercom. Approach, landing, passengers aboard, take-off, and the long, nerve-racking return flight – all went well – as Hysing-Dahl wrote on his de-briefing report: “The weather on the whole route was clear skies, good visibility. The operation was carried out without incident, the reception was very good, and had the procedure well taped. The ground was slightly bumpy but very firm.”

He was on the ground for less than a minute!

Wet Landing

The two “Norwegian” crews at Tempsford suffered no loss of life but one of Hysing-Dahl’s missions to France ended tragically:

It was one month after D-Day in 1944 – chaotic conditions on the Normandy coast – hardly ideal for two top-secret flights to deliver 6 French agents to a field south of the Loire. The first aircraft had taken off but as Per began to accelerate the engine coughed and spluttered. He had to abort the take-off. Pilot, passengers, and packages had to transfer to another Lysander. They were half an hour behind schedule. Safely through the battle cauldron they reached the landing area but, probably because they were so delayed, they were unable to locate the drop zone and had to return home. The three French agents were bitterly disappointed. As they neared the coast they could see the fires around Caen where the Germans were firmly resisting the British advance. Through the clouds, the coastline appeared but just when they imagined they were safe, flak began to thud around them. Heavier flak followed them as they twisted and turned in evasive action. Although not hit directly, splinters did their damage, puncturing the oil tank and destroying the radio. The engine held for a couple of minutes but cut out as they crossed the coast at 5000 feet. Lt. Hysing-Dahl thanked his lucky stars that he had recently been on a lifesaving course where he learned all about sea safety and rescue. The sea was moderately calm – Hysing-Dahl put the aircraft down “according to the book” and avoided a flip-over. As the landing gear drove into the waves the tail swung into the air and catapulted the three agents into the sea. For a moment the aircraft remained with its tail upright – and then disappeared under the waves. Per remembered nothing until he found himself in the water. The plane was gone and he could hear shouting from the agents somewhere in the darkness. They had nothing to hold onto and their heavy overcoats would soon drag them down. After he had got rid of his parachute he inflated a life raft – the automatic inflator didn’t work so lung power had to suffice. It couldn’t have taken more than a few moments but it seemed like an eternity. Then he pushed the life-raft towards where he thought the voices came from and just as he caught sight of them, one of them lifted his arm above the waves – and slid from view. The life raft, in reality part of the automatic ejection mechanism designed for the pilot alone, must now support three men. They spent the night huddled together, teeth chattering, occasionally washed by waves – but in good spirits knowing that they were in the main sea lane for traffic between England and the Normandy Beaches. Next morning they were picked up by an American vessel that took them to Plymouth. A second agent died in hospital.

Sunny respite

After his release from hospital and a short holiday with friends in England, Hysing-Dahl was posted to Ferry Command. Here he was teamed with fellow Norwegian, and previous Tempsford navigator, Trygve Kleve, in the less hazardous occupation of delivering new, two-engine Beauforts and Mosquitoes to Egypt. The aircraft were then flown to the Far East by pilots of the Indian Air Force. Though free from attack by enemy fighters, these ferry flights could still be dangerous – as when one motor suddenly cut out half way over the French Sahara desert. But the emergency landing and a three day forced rest gave them new experiences: An oasis of 160000 palm trees, a sand storm, an ancient desert fort, and a man-made garden, verdant with trees, bushes, and flowers – in sharp contrast to the seemingly endless golden sand. They worried about the motor stop, had they done something wrong? They were relieved when, on their return to England, they learned that the failure was due to a factory error.

Back to Tempsford

In the final months of the war the Resistance movements in Holland, Norway and Denmark, where German forces were still intact, continued to request supplies, ammunition, and weapons. In January 1945, Len Ratcliff, who had been Hysing-Dahl’s boss at Tempsford, was recalled from his Air Ministry post to Tempsford again where he became Wing-Commander of Squadron 161. One of his first actions was to “arrange” for Per’s transfer from Ferry Command to Tempsford. Similar “arranging” brought original crew members Dick and Ivor back into the fold. Per chose veteran Tempsford men “Maxi” as radio operator and “”Daisy” as mechanic. The old Halifax aircraft had been replaced by the bigger, and better armoured, Stirling machines. It took the crew only about an hour to feel at home in their new aircraft.

Their first assignment was to deliver a full load of supplies and equipment to the Resistance forces in Jylland. As they approached the coast they were enveloped by searchlights and battered by a barrage of flak. Surprised but unscathed they continued, found the drop-zone, watched as the containers and packages swung lazily under their parachutes, and then turned for home, flying low to avoid radar. Shortly after leaving the coastline a German night-fighter attacked from behind, wounding the rear gunner. Luckily the aircraft was not seriously damaged and the emergency procedures worked to perfection. Over Tempsford again, the airspace and runway were cleared for landing. Hysing-Dahl and the crew were close to exhaustion after the strenuous eight-hour flight and extra pressure from the enemy attack. On his approach, Per didn’t notice that the heavy side-wind had forced the aircraft too far left and the port wing looked as though it would crash into the control-tower. A calm, friendly, female voice came through his headset: “Aren’t you coming a bit too close to us now Skipper?” Full throttle, swing to starboard and disaster was averted – thanks to that calm, friendly, female voice. Per Hysing-Dahl put it this way: “This was my only trip to Denmark during the war. But it wasn’t the only time that the young women in the control-tower had helped the squadron’s aircraft to avoid tragedy. They were made of the same stuff as the British crew members I had flown with so many times.”

Last Flights

In Norway, the build-up of Resistance forces north of Bergen, code-named “Bjørn West,” depended almost entirely on drops by the aircraft from Tempsford. Per Hysing-Dahl had a particular affinity for these flights, as he knew, or had lived close by, many of the men on the ground. The final flight in support of “Bjørn West” took place on May 2. An open bonfire marked the drop-zone – a sure indication that the end of the war was just days away.

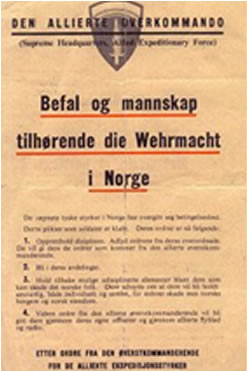

On the evening of May 8th the entire Tempsford personnel, about 1500 people, filled the huge main hangar for a victory celebration. As the party gathered steam, Wing Commander Ratcliff made his way to Hysing-Dahl and said “You and your crew should take it easy this evening. There’s a job for you tomorrow morning.” Per began to protest that the war was over – to no avail, Ratcliff was adamant: “Take-off 0900 hours tomorrow, destination Bergen, cargo: information leaflets”. The leaflets contained instructions from General Eisenhower about the surrender terms to the German forces in Norway. The first destination, “Festung Herdla,” was one of the most important German military bases on the west coast. The camp comprised 1000-1200 men, 30-40 aircraft, over 100 anti-aircraft guns and other artillery, a submarine base and a radar station. As Per and the crew circled they could see personnel running to the air-raid shelters. When the leaflets began to fall, many stopped and watched in surprise. Another group, unsure of the Stirling’s intentions, but true to German discipline, manned the anti-aircraft batteries. No shots were fired and as the last of the leaflets fell, the aircraft swung away to the south-west. 3

On the evening of May 8th the entire Tempsford personnel, about 1500 people, filled the huge main hangar for a victory celebration. As the party gathered steam, Wing Commander Ratcliff made his way to Hysing-Dahl and said “You and your crew should take it easy this evening. There’s a job for you tomorrow morning.” Per began to protest that the war was over – to no avail, Ratcliff was adamant: “Take-off 0900 hours tomorrow, destination Bergen, cargo: information leaflets”. The leaflets contained instructions from General Eisenhower about the surrender terms to the German forces in Norway. The first destination, “Festung Herdla,” was one of the most important German military bases on the west coast. The camp comprised 1000-1200 men, 30-40 aircraft, over 100 anti-aircraft guns and other artillery, a submarine base and a radar station. As Per and the crew circled they could see personnel running to the air-raid shelters. When the leaflets began to fall, many stopped and watched in surprise. Another group, unsure of the Stirling’s intentions, but true to German discipline, manned the anti-aircraft batteries. No shots were fired and as the last of the leaflets fell, the aircraft swung away to the south-west. 3

The hills surrounding Bergen, familiar, beloved landmarks to Per, unfolded beneath them bathed in bright, spring sunshine. In Bergen, thousands of people thronged the streets, flags in hand, flags flying everywhere. “A beautiful country in the warm flood of spring and a liberated people spontaneously overwhelmed with joy” are Per’s words. In the aircraft nobody had spoken for quite a while. Then Dick broke the silence, “You were not exaggerating Skipper, this is truly a beautiful country.” It is easy to understand why “Skipper” couldn’t trust his voice and simply nodded acknowledgement. Then, after a final swing over the crowds, back across the sea to England: “The country where our friends live.”

Interlude in Trondheim

At the same time that Per and his crew were heading for Herdla another Stirling aircraft left Tempsford for Trondheim on a similar mission. The aircraft didn’t return and next day, May 10th, Wing-Commander Ratcliff and Captain Per Hysing-Dahl took off in a Hudson to find out why. They searched the Møre coastline, the fjord entrance to Trondheim and then combed the countryside inland towards Lade. Flying over a small airbase they were surprised to see the missing Stirling aircraft peacefully parked on the runway – a runway actually too short for such a large aircraft. Their Hudson would have no problem however so they decided to land – with all armaments ready to fire in case of trouble. Instead of trouble, a German vehicle gently guided them to a parking space beside the Stirling. Young men of the Norwegian Resistance, armed with Sten-guns and rifles met them and explained that one of the motors had failed and the Stirling had had to make an emergency landing. British and German mechanics were checking the engine and later discovered that it could not be repaired, making a replacement necessary. The other crew members had already been caught up in the frenzy of freedom and were celebrating with the locals.

The Milorg men told Per that the German Air Force headquarters was located in a large house close to the base. As they spoke together, an official car drove up and the driver told them that the Commanding General would like to speak with them. In a hurried briefing, Len ordered Per to “represent the Squadron because you are in your own country again”.

They entered the commandant’s office in their oil-stained, well worn, and creased, flying jackets. In pristine uniforms and polished riding-boots: “Generalleutnant der Luftwaffe” Menshing and his adjutant Captain Kunath stood up, saluted, and remained standing at attention. Unfazed by the pompous appearance of the officers, Capt. Per Hysing-Dahl slid easily into his role as negotiator for the Allies. He reiterated the conditions of capitulation outlined by Gen. Eisenhower, demanded a guarantee of security for the two British aircraft, vehicles for transport to Trondheim and lodgings at the Britannia Hotel. After each point, Menshing clicked his heels: “Jawohl Herr Hauptmann”. Everything would be taken care of promptly.

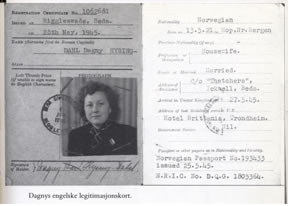

In Trondheim, after celebrating with some of the local Milorg men, they checked into the Britannia Hotel for a well-earned rest. Per telephoned his mother and his fiancé Dagny before turning in for the night. Next morning, on the way back to England, the radio operator sent instructions for a new motor to be loaded into a Stirling as soon as possible.

Next day, on May 13, Per and the crew landed safely with the new motor. Per telephoned his fiancé again and discovered that she had already left Bergen and was on her way via Oslo to Trondheim by train. The journey was tedious, troublesome, and took 60 hours – but then, what are 60 hours when one has waited 4 years? At a dinner aboard HMS Broadway a couple of days later, the captain of the ship asked Per and Dagny if they were married. At the negative reply the captain insisted that they avail themselves of his authority to perform the wedding ceremony. With ship’s officers and men as “relatives” and witnesses, Per and Dagny became Mr and Mrs. Two days later they were married again in Trondheim Cathedral. A freedom-happy, anonymous ‘Trønder’ (a man from Trøndelag) hosted the wedding reception!

Dagny Hysing-Dahl’s Identity Card

When the new motor had been installed in the stranded Stirling Per was recalled to England. What to do – must he leave Dagny again? Carrying civilians in British military aircraft was strictly prohibited. The Royal Navy came to the rescue, in the shape of Captain P. Ruck-Keene who had recently arrived to take command of all the Allied forces in the area. Per and Dagny visited Capt. Ruck-Keene at his office in the Britannia hotel. When he heard Per’s dilemma he said “take her with you” – and leaned back in his chair – problem solved. But Per had to point out that it wasn’t so easy: “What happens when we get to England – immigration laws and things, we will certainly have problems?” “Problems? Young man, there are no problems that the Navy cannot overcome” was the reply.

With that, he wrote a few lines on a piece of paper and told Per that this was for the officials on the other side of the North sea. He gave the paper to Per with the words: “My dear friend, there are few people who can stop me!”

And so it was – almost. The immigration official did have a problem – who was Ruck-Keene? But a quick telephone to London gave him the answer – and Dagny was free to enter the land her husband had served so well.

During the sojourn in Trondheim a journalist, probably intoxicated with the joy of a newly freed press, interviewed one of Per’s crew who said that they had on board one of the RAF’s best Norwegian pilots – Per Hysing- Dahl. He continued: “Hysing-Dahl’s British colleagues have the highest regard for his courage and capabilities as a pilot. He has received every military honour possible and would have been promoted to major long ago but for the relative small size of the Norwegian air forces. As for Norwegians in general in England – God bless them, I haven’t met one who wasn’t a gentleman.” 4

For his war services Capt. Per Hysing-Dahl he was awarded the War Cross with sword, St. Olavs Medal with oak leaf, the British Distinguished Flying Cross with bar, the French Croix de Guerre, the War Medal, and the Participation Medal. In 1984 the city of Blois made Per Hysing-Dahl an Honorary Citizen and unveiled a plaque commemorating the important flights from Tempsford.

For his war services Capt. Per Hysing-Dahl he was awarded the War Cross with sword, St. Olavs Medal with oak leaf, the British Distinguished Flying Cross with bar, the French Croix de Guerre, the War Medal, and the Participation Medal. In 1984 the city of Blois made Per Hysing-Dahl an Honorary Citizen and unveiled a plaque commemorating the important flights from Tempsford.

Per Hysing-Dahl continued to serve his country after the war. For many years he was a successful businessman and then politics called. He was elected to Parliament in 1969 and served as Speaker of the House from 1981 to 1985.

Return to France

During his flights from Tempsford, it is easy to understand that Capt. Per Hysing-Dahl often thought about the men and women on the ground who planned the reception, collection, hiding and distribution of the supplies they dropped and the agents they delivered and picked up. Gradually, through many years of peace, the troublesome memories and impressions of a terrible war receded but he continued to think about his unknown colleagues in France. So, in 1962, with tent and sleeping bags he, his wife, and 3 daughters set off on a tour of discovery in their old Peugeot.

After a side-trip to visit pilot-colleague Bob Large in England and a stop to see the Eiffel Tower, they reached the Loire and started their search. It was not easy because they had neither names nor information of any kind. Speaking slightly better than high-school French, they went from police station to town hall, to post-office in village after village in the Loire valley asking if anyone knew anything about the Resistance groups that had received the supply drops during the war.

Finally they were directed to Théo Bertin, a farmer who lived in the fertile valley between the Loire and the Cher, about 20 km south of Blois. His farm, “Maison Rouge” produced corn, vegetables, grapes, and tobacco. Bertin’s wife had died before the war started so his mother-in-law, “grand-mère” looked after him, kept the house in order, and even helped during the preparation for the night-time drops. Bertin was the leader of one of the many Resistance groups in the area’s flat, open landscape. Only an occasional small forest provided any cover, and drop-zones were often placed close by.

Just as in Norway, information about the drops came over the radio from the BBC. Théo remembered one such message: “Ces pieds de cochons se mangent farcis!” (These pig’s trotters can be eaten minced!). “Grand-mère” heard the message, quickly hid the radio, and ran out to warn Théo. Then she went into the kitchen to make sandwiches for the men, check the torches, and keep an eye on the clock. Towards midnight all the men had arrived and were at the drop-zone, waiting and listening. Hysing-Dahl remembered that this particular night the Halifax was loaded with packages and that two agents were dropped. “Yes, but you dropped them too early” said Bertin. They ended up among the trees – it took several hours to find them and hide the evidence that they had ever been there at all. Hiding the evidence was important because the Germans knew about the drops and were constantly patrolling the area – by road and from the air. Because of the air reconnaissance, Bertin disliked white parachutes and the white labels stuck onto the containers and packages. “White parachutes on the ground could be seen for miles from the air and those white labels easily blew off and were a sure sign to the enemy if left lying around.”

Per and his family spent several days in Blois talking to Théo and other members of the Resistance. One of them, the mayor of Blois, Pierre Sudreau, had been arrested, tortured, and sent to Buchenwald in 1943 – he was one of the few who returned. He became an active politician, filling important posts in Paris as well as his municipal duties in Blois. Another, Raymond Casas, was only 14 years old in 1940 but he joined a Resistance group supplied by the flights from Tempsford. After the war he wrote two widely acclaimed books about the Resistance movement and founded a Resistance museum in Blois. Théo himself managed to avoid capture and between drops he kept up his sabotage speciality: blowing up railway tracks and power lines.

In 1984 Per and Dagny Hysing-Dahl were invited to attend the commemoration of the 1944 liberation of Blois. At the Norwegian Embassy in Paris they met their hosts from Blois, represented by the Mayor of Luzillé, Golbert Buron and then drove down to the Loire valley.

In Luzillé, flags waved in the breeze from every building, people thronged the streets, speeches were maid, wreathe were laid, and the flags of Norway, France and Britain decorated the long lunch table. It turned out that M. Buron’s farm was close to the drop-zone of the unusual “triple” operation in May 1944. A tall mast with the three allied flags marked the site of the drop-zone. The landowner, “an elderly, friendly lady”, remembered the event clearly and the re-union here made a strong impression on Per.

In Luzillé, flags waved in the breeze from every building, people thronged the streets, speeches were maid, wreathe were laid, and the flags of Norway, France and Britain decorated the long lunch table. It turned out that M. Buron’s farm was close to the drop-zone of the unusual “triple” operation in May 1944. A tall mast with the three allied flags marked the site of the drop-zone. The landowner, “an elderly, friendly lady”, remembered the event clearly and the re-union here made a strong impression on Per.

At a Town Hall reception in Blois, Per told the Mayor, Pierre Sudreau, how important the Town Hall and Cathedral had been as landmarks for the pilots from Tempsford and how much they admired the men and women waiting on the ground. The Mayor replied that the pilots were the heroes – “Flying by the light of the moon, without radio navigation, without information about power lines, or other obstructions – And who would be waiting for them, Gestapo or Resistance forces?” Later the Mayor unveiled a plaque on the wall of the Town Hall that commemorated the flights and the landmarks.

Dagny and Per Hysing-Dahl

In subsequent visits to France, Per and Dagny Hysing-Dahl renewed old friendships and forged new ones. They felt a close kinship with all but only Raymond Casas managed to visit the Hysing-Dahl home near Bergen. Per always intended to write to every one of the men and women they had met in France but unfortunately, just when he had time, he became ill and the task was unfulfilled.

Instead, his books, with their concise, heartfelt, and warm personal descriptions, are his legacy and his appreciation.

Visit to Washington D.C.

On July 26 1985, Speaker of the Parliament Per Hysing-Dahl visited the United States Vice-President George Bush in his White House office. They had met before, in 1983, when George Bush had been a guest in Oslo. At that time they had found common cause in support of the western alliance, joint defence, and shared burdens. Their views had not changed so in Washington their conversation was congenial and relaxed. On the same day, the Prime Minister of China was scheduled to visit the White House. Not wanting to keep the Vice-President from his other appointments, Hysing-Dahl made a move to end the meeting.

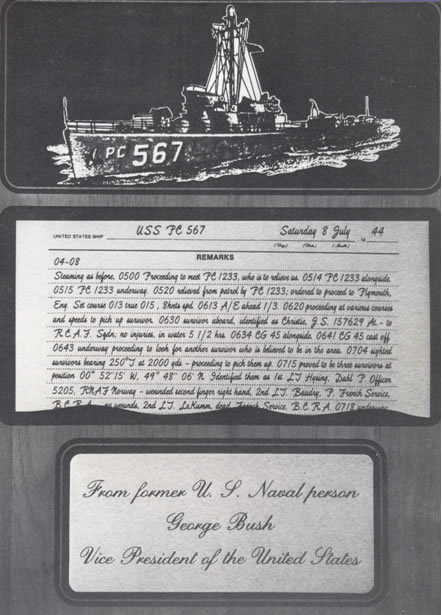

George Bush, however, had other ideas and he reminded his guest of an event that had taken place 40 years earlier when an American vessel, heading for the Normandy beaches, had picked up Hysing-Dahl and two Frenchmen from the cold waters of the English Channel. He then presented a cherry-wood plaque to Hysing-Dahl. The plaque featured a silhouette of the rescue vessel, Patrol Craft 567 engraved in bronze. Underneath was an authentic extract from the ship’s log in which the officer in charge described how they first saw the survivors, how they brought them aboard and the name, number and rank of each survivor and finally, the dedication from the Vice-President.

George Bush, however, had other ideas and he reminded his guest of an event that had taken place 40 years earlier when an American vessel, heading for the Normandy beaches, had picked up Hysing-Dahl and two Frenchmen from the cold waters of the English Channel. He then presented a cherry-wood plaque to Hysing-Dahl. The plaque featured a silhouette of the rescue vessel, Patrol Craft 567 engraved in bronze. Underneath was an authentic extract from the ship’s log in which the officer in charge described how they first saw the survivors, how they brought them aboard and the name, number and rank of each survivor and finally, the dedication from the Vice-President.

Per Hysing-Dahl was speechless and deeply moved by this presentation. In the two years since they had met in Oslo, the Vice-President had retrieved full details of the rescue from State Archives. A more time-consuming, thoughtful and personal gift would be difficult to imagine.

Epilogue – from Dagny Hysing-Dahl, November 2008:

Per died on April 7 1989. In December 1989, together with grandchild, Jostein (17), I visited a relative, Betty, in Boynton Beach, Florida. We went into a restaurant to buy some ice-cream and began talking to a man sitting nearby. He asked where we were from and the usual pattern of questions and answers followed. Betty told him that my husband had been a pilot in the R.A.F. during the war. The stranger said that he had served in the U. S. Navy and I told him about Per’s rescue by the US Patrol Craft. As I did so the man nodded and smiled, almost secretly, as if to himself: “Yes, yes” he said, “I remember that voyage well – I saw them being hoisted aboard.”

De-briefing reports.

| Lt. Per Hysing-Dahl. De-briefing reports. Tempsford Airfield. 1943 -1945 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Date |

Name |

A/C |

Area |

Result | Elapsed time/ (time over target) |

Comments |

| ? | Tom 26 | France | NC | GEE very little help | ||

| 43.10.11 | Grouse | H | Kongsberg | NC | Haugland /Sønsteby | |

| 43. 10.15 | Grouse | H | Kongsberg | NC | Haugland/Sønsteby | |

| 43.11.12 | Grouse | H | Kongsberg | NC | Haugland/Sønsteby | |

| 43.11.17/18 | Grouse | H | Kongsberg | C | Haugland /Sønsteby | |

| 43.10.18/19 | Lapwing | H | Røros | NC | 10.05 (30) | Bad weather |

| 43.10.21/2 | Lapwing | H | Røros | C | 4 men, supplies, blind drop | |

| 43.11.7/8 | Bob21 | H | France | C | 5.54 (6 mins) | 20 pigeons Clear Skies |

| 43.11.9/10 | Dragon | H | France | C | 6.40 | Lights not in triangle |

| 43.11.9/10 | Peter31 | H | France | NC | 10/10 cloud below | |

| 43.11.12/3 | Goldfinch | H | Norway | NC | 5.45 (5) | See below |

| 43.12.10/11 | Njord 11 | H | Norway Tyrifjord |

C | 8.38 (3) | Light & heavy flak from about 3 Bofoss type guns |

| 43.12.10/11 | Uranus | H | Norway | With Njord | Agent jumped when told | |

| 43.12.20/1 | Brasenose III | H | France | C | 6.43 (4 mins) | Passenger jumped when ordered. |

| 43.12.20/1 | Calendine | H | France | NC | Triple op | With Brasenose/Vienne |

| 43.12.23/5 | Vienne | H | France | NC | 6.43 (9) | No reception |

| 44.1.4/5 | Arquebus | H | Norway | C | 7.50 | |

| 44.1.6/7 | Acolyte | H | France | NC | 9.00 | 2 runs, no reception |

| 44.1.6/7 | Matisse | France | C | ? (23) | Leaflets and pigeons | |

| 44.3.3 | Fureur | France | C | 5.45 (5) | Field Bumpy. | |

| 44.3.15 | Alexandre | Normandy | NC | 2.15 | “H-D did his best” CO | |

| 44.4.5/6 | Lilac | France | C | 4.40 (5) land | “very satisfactory operation”- CO | |

| 44.4.11/2 | Holyhock | L | France | C | 5.10 (5) land | Field very firm |

| 44.5.3 | Framboise | France | C | 5.5 (5) | VG Reception. Loire | |

| 44.5.3/4 | Pipe | L | France | C | 5.00 (5) | “my considered opinion ground unsafe” CO agreed |

| 44.5.9/10 | Mineur | L | France | C | 4.15 (.) | 8 “Joes” – unusual “Triple” |

| 44.6.7/8 | Eiger | Germany | C | 8.55(2) | Double op with Messenger | |

| 44.6.7/8 | Messenger2 | H | France | NC | 8.55 (7) | No reception. 2 enemy fighters above us – no action |

| 44.07.7/8 | Palaise | L | France | NC | Double op | Missing – see below. |

| After crash-landing in the British Channel, Hysing-Dahl was transferred to Ferry Command until 1945 when he was recalled to Tempsford. | ||||||

| 45.4.22/3 | Rump | S | Norway | C | 7.55 (7) | Hamlegrø Lake – Voss |

| 45.4.23/4 | Checkers1 | S | Germany | C | 3.08 | Joes jumped well |

| 45.4.24/6 | Vet 15 | S | Norway | C | 6.19 (01) | The agent jumped well – Haugland? |

| 45.5.2/3 | Blinkers2 | S | Norway Bjørn West |

C | 8.18 | The other a/c seen making abort |

‘Joes’ Secret Agents – either dropped, landed or picked up

‘CO’ Commanding Officer (Wing Commander)

A/C Aircraft: H Halifax S Stirling L Lysander

C Completed NC Not Completed

GEE Electrical Position Indicator

Goldfinch – Captain’s Personal Report:

S/Inner engine cut at 2130 hrs on outward journey, about 50 miles before reaching Norwegian coast. Prop was feathered for remainder of trip. A/C continued to within 30 miles of target then gave up owing to weather. All guns were u/s (useless) from the time they were tested on crossing the English Coast outward. The gunner worked on them throughout the trip without success.

S/Inner engine cut at 2130 hrs on outward journey, about 50 miles before reaching Norwegian coast. Prop was feathered for remainder of trip. A/C continued to within 30 miles of target then gave up owing to weather. All guns were u/s (useless) from the time they were tested on crossing the English Coast outward. The gunner worked on them throughout the trip without success.

Flekkefiord 2327 hrs 5500 ft. One large M/V (Marine Vessel) about 8000 tons and 6 others anchored off the town.

Palais On this report is written: ‘Missing’ – with a difficult to read explanation. In his book, “Wings over Europe”, Lt. Hysing-Dahl tells the story, partially reproduced above.

1 Forgotten Voices P.89 Pilot Officer John Charrot. Halifax observer/bomb aimer, 138 (SD) Squadron, RAF.

2 www.tempsford – see link below.

3 Herdla Museum contains a section dedicated to this special flight.

4 Unidentifiable Newspaper clip received from Mrs Dagny Hysing-Dah